The Porcupine's Quill

Celebrating forty years on the Main Street

of Erin Village, Wellington County

BOOKS IN PRINT

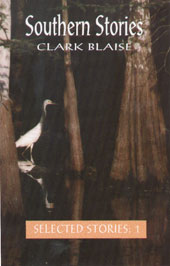

Southern Stories by Clark Blaise

The stories collected here in Volume One are among the earliest in Blaise’s forty-year publishing career. The experience of Florida -- particularly the underdeveloped north-central areas close to modern Disneyfied Orlando -- profoundly affected a ‘Yankee’ child with Canadian parents. The Florida Blaise describes is little-changed since the Civil War.

The stories in this volume trace a young writer’s journey towards his life’s work. By the close of his Florida experience, he has discovered a way of integrating his Canadian, and especially his French-Canadian, background into a sub-tropical foreground.

Included are two very early stories, ‘A Fish Like a Buzzard’ and ‘Giant Turtle, Gliding in the Dark’, which have not previously been published in book form. Southern Stories assembles the best of Clark Blaise’s early work in one collection. His powerful writing is as relevant to our times now as it was when these stories first appeared. Included here are stories from A North American Education, Tribal Justice, Man and His World and Resident Alien.

Review text

This unique collection of short stories from the critically esteemed Canadian author Clark Blaise revitalizes the American South as a site of discovery, despite its narrative history of being one of the most popular subjects in modern English story telling. Blaise presents a setting that holds few vestiges of the south that we have all come to expect. Blaise understands his audience’s familiarity with these well-worn clichés and discourages our reliance on them. Southern Stories are slow moving tales of growing up poor in 20th century America. Blaise’s distinct style appears slowly within this collection, as he guides us through the unusual recollections of children living in the south. These are young boys who have clearly experienced other cultures, and indeed, a restrained yet influential Canadian perspective emerges. This slant is often subtle, appearing for example as a reference to a single French-Canadian character, or the protagonist’s fascination with snow and Florida’s lack of it.

Southern Stories do not have the pace of typical narratives. There does not exist here a sense of climax. In short, Blaise requires his readers to become companions for his characters, to walk with them, and spend a day in their life. The author is making introductions for his audience, allowing us to meet and to understand these southern boys and their families. These are stories clipped from human experience that do not have a resolution: primarily because there does not appear to be a problem. Recalling the experiences that recreate for us how others connect with their world does not need a manufactured structure of ‘beginning, middle and end’, and Blaise eases us into this anti-structure painlessly.

The stories do, however have a loose chronological form to them. For example, the first several stories deal primarily with the relationships between young male friends, as well as young boys with their parents. A particularly revisited relationship here is that between mothers and their sons. In Broward Dowdy for example, Blaise looks at two mother/son couples separated and contrasted by class level (one are the family of a soldier and the other lives in abject poverty as a family of roaming pecan pickers). Later in the collection, Blaise begins to introduce his developing characters’ awkward, adolescent sexualities. The author does so with an intensely candid examination of young men’s new found urges. Take this excerpt from A North American Education where a young boy experiences a nudie-show for the first time:

‘There was no avoiding the bright pink lower lips that she had painted; no avoiding the shrinking, smiling, puckering wrinkled labia. ‘‘Kiss Baby?’’ she called out, and the men went wild. The lips smacked us softly. The Princess was more a dowager, and more black than brown or yellow. She bent forward to watch herself, like a ventriloquist with a dummy. I couldn’t turn away as my father had; it seemed less offensive to watch her wide flat breasts, and to think of her as another native from National Geographic. She asked a guard for a slice of gum, then held it over the first row. ‘‘Who gwina wet it fo’ baby?’’ And a farmer licked both sides while his friends made appreciative noises, then handed it back. The princess inserted it, as though it hurt, spreading her legs like the bow-legged rodeo clown I’d seen a few minutes earlier’.

Although this (and other) representations of women in Southern Stories can be characterized as less than PC; Blaise creates a meaningful context for these images through the eyes and mental understandings of young men who are products of their cultural environment. The honesty and the reality of how things appear to children reflects the often brutally unfair and degrading ways in which we relate each other here in North America. Blaise exposes class and gender inequalities through the observations of perceptive young men. What makes these stories additionally telling is that these children are not the average, static American or Canadian kids. Borders have taken on a more fluid nature for these characters, which position them to reveal the American south from an appealingly unusual perspective. The author appears in favor of this young, unsophisticated, cross-cultural viewpoint, and for good reason. These characters show the ways in which our most minor, simplistic and unremarkable experiences can reveal an often elusive basic truth.

—Anne Riley, CBFU Radio Niagara

Review quote

‘... fascinating studies of the Global Village in the late 20th century.’

—The Toronto Star

Review quote

‘[a] fresh, idiosyncratic approach to what the short story can and should do.’

—Books in Canada

Review quote

‘A born storyteller ... a writer to savour.’

—The New York Times

Review quote

‘The pieces collected ... display the sure hand of a skilled writer. And though Blaise is unflinching is his portrayal of the poverty and backwardness of the post-war American South, a muted sense of wonder leads the reader over some very rough terrain.’

—James Grainger, Quill & Quire

Review quote

‘As novelist Fenton Johnson notes in the introduction to this book, Blaise’s portrayal of a dirt-poor South haunted by history belongs to an American literary tradition that includes Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor and Eudora Welty. What needs to be added is that this Southern Gothic tradition has tendrils that reach all the way up to Canada. Aside from Blaise, there have been many reverse carpetbaggers, Southerners who have headed (or returned) north such as Leon Rooke, Douglas Fetherling and Elizabeth Spencer. Moreover, many prototypically Canadian writers such as Alice Munro learned their craft at the feet of Southern masters. Like the American South, Canada has been a poor, rural land suspicious of outsiders and technological progress for most of its history. It’s no accident that at the end of the American Civil War, confederate leaders such as Jefferon Davies ended up in Canada. Progressive and enlightened Canadians might not like to think so, but there is a deep emotional affinity between Canada and the American South.’

—Jeet Heer, National Post

Review quote

‘Canadian Blaise (author of twelve previous books, including Lusts and If I Were Me) gathers thirteen early short stories, all set in the grim, steaming poverty of north-central Florida in the 1930s, 40s and 50s. Autobiographical in inspiration, they reflect Blaise’s own childhood as an intelligent child of Canadian parents struggling to make their way in a world of rednecks, migrant workers, tarpaper shacks, swamps, and privation. Carefully worded and beautifully constructed, these tales reveal Blaise’s talent as a storyteller, as well as his dark view of human nature. In ‘‘A Fish Like a Buzzard,’’ two quarrelsome young brothers go fishing on a Florida lake, but only one may come back. In ‘‘A North American Education,’’ a father takes his son to a county fair peep show to teach him about sex, but the lesson has unpleasant consequences. ‘‘The Fabulous Eddie Brewstera,’’ a clever story of clouded family loyalty, suspicion and wartime secrets, is one of the collection’s strongest. Entries tell of infidelity, racism and religious intolerance -- of a boy’s deep and inexplicable admiration for his father, driven by ‘‘blind lusts,’’ and a family’s betrayal and their subsequent retreat to escape their failure and humiliation. Though Blaise’s volume is a superb example of controlled, elegant writing, readers should not expect to find many moments of humor or happiness. As Johnson notes in his introduction, ‘‘an open-ended terror underlies these stories’’ [and] ‘‘the characters never fully comprehend the forces that have been brought to bear upon them.’’ ’

—Publishers Weekly

Review quote

‘Those who have read Blaise will likely be familiar with his non-fiction bestseller Time Lord, not the four volumes of his Collected Stories that have sold somewhere in the low hundreds. Though he became a member of the Order of Canada in 2009, Blaise has never won a GG. And yet his body of work -- and one can speak of it as a coherent body -- is an entertaining and profound monument to the craft of the short story.’

—Alex Good & Steven W. Beattie, The Afterword

Introduction or preface

The world is a continuum of borderlands -- when Canadian French is so commonly spoken in Maine and Mexican Spanish in California, what meaning has the invisible dotted line? And yet the demarcation of ‘here’ versus ‘there’ is among the richest of literary territories, probably because it offers such opportunity to juxtapose the self with the other.

For more than twenty years I have turned to Clark Blaise’s writing as I might hire an interpreter in a foreign land -- someone to help me understand my own borderlands, the rich and scary places where I am brought up against the shifting construction of identities I call myself. Clark Blaise is of my America and apart from it, at once a Canadian and a U.S. citizen, Yankee and Southerner, native and exile -- a global citizen before we invented the phrase to describe the condition.

Blaise’s childhood embraced the most radically different of North American subcultures: Canada relying on its European heritage to distinguish and distance itself from the U.S., and an American South fiercely disdaining all that smacked of Yankees and the North. He is a chronicler of paradox -- which as any fictionist knows is where the real goods lie -- writing fictions of contradiction set in landscapes divided North from South, rich from poor, white from black, insider from outsider. He is the immigrant’s legitimate prophet -- understanding ‘prophet’ not as one who foretells the future but as one who (like Isaiah or Jeremiah) offers an unflinching portrait of the realities of the present. In these stories, this encompasses a description -- sometimes poignant, often harrowing -- of what it means to be an intruder into the sullen culture of the white communities of the South, a culture of defeat, so vastly insecure that its principal source of validation lies in victimizing any and all who are different, foreign, ‘other’ (even when, as is often the case with African-Americans, the ‘other’ constitutes a numerical majority).

No landscape offered the prophet richer potential than that of the Old South in its last-gasp days -- on the verge of becoming, for the second time in its history, the destination of Northerners seeking the quick buck, except that this time the carpetbaggers would be welcomed with open arms, and for better and worse would settle in to stay. The American South of Clark Blaise’s stories -- the South in which I grew up -- was teetering at the precipice of its century-late tumble into the modern world; on the verge of transforming itself -- or, more often, being transformed -- from a culture that measured time by generations into one that measures it by the time card and the clock. Blaise writes of that transition from the most peculiar and fascinating perspective -- the outsider’s timeless time, the immigrant’s placeless place.

The great religious historian Mircea Eliade describes how Judeo-Christian civilization invented linear time. Earlier cultures envisioned time as a circle or spiral or sphere in which history endlessly repeats itself; then the late Jewish prophets initiated the conception of a linear, chronological progress toward apocalypse -- the end of time, after which the saved and the damned would dwell in some eternal place, a place outside of time. Taken up by Christianity, that idea achieved its apotheosis in the American experiment. The founding of the U.S. sprang from and requires the notion of perfectibility, of progress (‘our most important product’) toward some city on a hill which, once attained, will constitute the end of time and the beginning of some new, timeless eternity.

The South of Blaise’s stories -- rural, poor, obsessed with the fantasy of creating victory wholecloth from the tatters of defeat -- still dwelt in something closer to that ancient, circular time. Into this humid, unchanging landscape walks a Northerner of Canadian ancestry, a creature more exotic than even a European because he seems in the face of manifest destiny and good sense to have stubbornly chosen his fate (as a schoolchild I looked at the long horizontal stretch of Canada and wondered why its citizens didn’t concede the obvious, throwing in the maple leaf flag and becoming the fifty-first state).

Probably because of his status as outsider, Blaise seems always to have resided in and written from non-linear time. Even as the American publishing mainstream was adhering to chronological, apocalyptic time -- the action rising in a strong, consistent line to a dramatic climax, after which the author quickly and gracefully exits -- Blaise was writing round, seamless narratives that share more with the Southerner Eudora Welty or the Canadian Alice Munro than with the Mid-Atlantic Seaboard ideal. These stories circle back on themselves -- they dwell not in chronological but in circular time, the time not of the railroad engineer but of the priest and the poet. They have their roots in a mythological time, even as one senses the vastness of the change looming on the horizon, and the protagonist’s place caught in between. ‘I’m still a young man, but many things are gone for good,’ says a character in A North American Education, straddling in a single sentence the boundary between the Southerner’s obsession with memory and the Northerner’s obsession with progress. In ‘Notes Beyond History’ -- the title is telling -- the anonymous bureaucrat of the New South looks from his eighth-floor office over the (now landscaped and manicured) lake of his childhood and considers how ‘not only has the lake been civilized, but so has my memory, leaving only the memory of my memory as it was then ... change merely reflects the unacknowledged essence of things. That’s what history is all about.’ These are stories of people in motion in conflict with people in stasis -- immigrant stories written for a nation of immigrants, by a writer who is of and apart from the country of which he writes.

Reality, Nabokov wrote, is the only word that ought always to be enclosed in quotation marks. Saying the same thing differently, my storytelling father once told me, ‘I never met a fact that couldn’t be improved with a little exaggeration.’ The ‘improvement’ of which my father spoke is of course art, an improvement that paradoxically renders it more, not less, representative of truth (as distinct from ‘reality’).

Reading these stories decades after their publication (the earliest was completed in 1958), I’m struck by how they are postmodern well before the term came into vogue, so postmodern they evoke Western fiction’s roots in Smollett, Richardson and Sterne. The early stories have enough autobiographical detail to read like a memoir -- until some quirk reveals the artist’s hand, shaping the raw and disordered clay of experience into truth. As with those eighteenth-century predecessors, the fiction sustains no artificial distinction between reality and imagination; the story is the reality, with one critical difference -- these protagonists have known the Holocaust and the bomb; they are in full possession of the old wisdom of the fall. Amid the frantic cheerleading of the Age of Reason become the Age of Advertising, they illustrate and illuminate the tragic destiny of human fallibility. To read these stories is to journey into the synapses of memory, to understand how its flawed and warped mirror is reality, how we take our affirmations from others to construct identities that are not so much whole and distinct as shifting images in an ongoing, ever-changing collage composed of our responses to the ever-changing world.

An open-ended terror underlies these stories, the sense of something truly awful always on the verge of happening. Even the earliest stories focus on process -- there are no neat epiphanies here. The boy falls into the alligator-infested water, but we do not learn his fate; the sheriff (coming, in contravention of his official duties, to wrack violence?) cruises by but does not gain entrance. In a way that’s uncomfortably true to life, the characters never entirely comprehend the forces that have been brought to bear upon them.

In his later writing Blaise moves on from this particular geography, but he would continue to explore the themes and techniques first presented here -- a fascination with the relationship between time and memory, an affection for the darker side of human encounters in which nothing is what it seems and where men’s plans often lead to disastrous consequences they could not have foreseen. ‘The Love God’, a later story, represents a logical progression in its exchange of the illusions of social realism for the more straightforward illusions of the world of fantasy. A shape-shifting son of a stud stallion becomes a media consultant who lives in suburban Atlanta, until his father returns as a woman to seduce him back to his true vocation, which is to liberate himself and others through sex.

Going beyond the weirdly inflexible logic of the clock, Blaise’s pre-modern postmodern imagination has shape-shifted into magical realism -- a transmogrification accomplished in their very different ways by William Faulker, Flannery O’Connor, and Welty. Reynolds Price wrote of Eudora Welty that she was recasting Ovid in Mississippi, but he could easily have extended the observation to a whole raft of Southern writers, among whom Blaise has a legitimate if uneasy place -- constructing a reality with the sureness and aplomb of the Southern storyteller, but in the particular and elegant Commonwealth diction of the Canadian.

I grew up in rural Kentucky, ninth of nine children. None of my two centuries of Kentucky-born ancestors had lived outside my home county; now -- in one generation -- we are scattered to the corners of the continent. Like most Americans I live between wanderlust and nostalgia; we long to be on the move even as we create and follow with unparalleled devotion the cult of home -- with ‘home’ defined as that imagined and imaginary place where nothing changes. That no such place exists only strengthens its hold on our imaginations, leading us to construct national identity -- and with it social, economic, and political policy -- around the increasingly untenable illusion of the clapboard house whose happily married inhabitants are as white as their picket fence.

That we are obsessed with home makes perfect sense, of course -- those people farthest from any sustainable experience of home romanticize it most -- but on the whole U.S. writers are too immersed in the illusion to perceive and write out of its contradictions; our very adjective for citizenship (‘American’) presumes that we and the continent are coterminous, as if no America exists outside the lower forty-eight states. To understand ourselves fully we must turn to outsiders -- to immigrants sufficiently removed from the vastness and power of the U.S. to perceive its illusions, and in writing of them to give us a glimpse of the truth that lies on their other, darker side.

Reading Clark Blaise’s stories from the South is like visiting a retrospective of a brilliant painter -- one sees in the earliest work the themes that gradually emerge and sharpen. This is the great joy of writing, enough to offset its burdens. Across a lifetime a writer’s words, diligently and honestly compiled, allow his essential character to emerge, and as it emerges to shape what comes behind, a symbiosis between art and nature in which the writer shapes the clay that shapes himself. Across these stories the reader has the great privilege of witnessing the writing become as transparent as glass, leaving the writer standing revealed to himself and to the world in his nakedness. In that state of grace he offers a glimpse of the truth, which, if we have the courage to seize it, is the instrument of our freedom. -- Fenton Johnson

Clark Blaise has taught in Montreal, Toronto, Saskatchewan and British Columbia, as well as at Skidmore College, Columbia University, Iowa, NYU, Sarah Lawrence and Emory. For several years he directed the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. Among the most widely travelled of authors, he has taught or lectured in Japan, India, Singapore, Australia, Finland, Estonia, the Czech Republic, Holland, Germany, Haiti and Mexico. He lived for years in San Francisco, teaching at the University of California, Berkeley. He is married to the novelist Bharati Mukherjee and currently divides his time between San Francisco and Southampton, Long Island. In 2002, he was elected president of the Society for the Study of the Short Story. In 2003, he was given an award for exceptional achievement by the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and in 2009, he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada ‘‘for his contributions to Canadian letters as an author, essayist, teacher, and founder of the post-graduate program in creative writing at Concordia University’’.

The Porcupine's Quill would like to acknowledge the support of the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. The financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) is also gratefully acknowledged.