The Porcupine's Quill

Celebrating forty years on the Main Street

of Erin Village, Wellington County

BOOKS IN PRINT

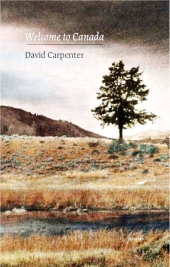

Welcome to Canada by David Carpenter

Get out of the house, get out of town, go west, go north, head for the wilderness and suffer like a true Canadian. David Carpenter will take you there. His prose has more pop than Orville Reddenbacker.

David Carpenter’s stories often begin in a comic mode, and the voices of the characters, their accents, tones and peculiar vocabularies, are brilliantly caught. But what begins as comedy can frequently veer into fierceness, farce, regret or indignation. On these unpredictable journeys, we meet an amorous Texas millionaire and his native fishing guide, a cow named Turkle, a farm girl who talks to bears, a kokum who speaks with departed spirits, a German scholar with a taste for saskatoon berries, an all-Jewish football team that takes a chance on a goy, an aboriginal folksinger who finds love in a laundry dryer and loses it in a motel, a monster northern pike named Adolph, a shy roaring-twenties photographer who hates dogs and loves peppermints.

Most of Carpenter’s characters are city people who find themselves out in the bush with the bear, deer, elk and wolves, and sometimes even Windigo. Carpenter has a strong relationship with the wild country of the northern boreal forest, the Saskatchewan prairies and the Alberta foothills. His prose is protean. It shifts into the minds and the voices of his characters and gathers the reader along to unexpected destinations: grief, joy, or a nicely shaded triumph often involving love, escape or an unexpected kind of revelation.

Since 1975, with the exception of four years split between Toronto and Vancouver Island, Carpenter has lived and written in Saskatoon. He has been nominated and won numerous literary accolades for his work, including fiction, nonfiction and poetry. Until recently he was fiction editor for Grain Magazine.

2010—ForeWord Magazine Book of the Year,

Runner-up

2010—Independent Publisher (IPPY) awards,

Winner

2010—Saskatchewan Book Award (Fiction),

Shortlisted

2010—Saskatchewan Book Award (Book of the Year),

Shortlisted

2010—Saskatchewan Book Award (Saskatoon),

Shortlisted

Table of contents

Foreword: You Are Now Entering Carpenter Country

Welcome to Canada

Turkle

The Snow Fence

The Ketzer

Protection

Meeting Cute at the Anger Motel

Luce

This Shot

Review text

Understated and poignant, David Carpenter’s Welcome to Canada: Stories collects a number of flawed and beautiful characters who illuminate the fragility of human nature. The isolation, unpredictability, and grace of the Canadian wilderness sets the atmosphere and tone for these brilliantly crafted short stories, while the characters, many of whom are city folks confronted with the life and inhabitants of the Canadian bush, discover the meaning of redemption in situations that challenge their beliefs.

The stories, a combination of short and long form, illustrate Carpenter’s uncanny ear for humor and reflect how geography and culture are reflected in the dialects and cadences of speech. In the title story, ‘Welcome to Canada,’ Carpenter superbly depicts the phonetic quirks of an adventure-seeking Texan named Lester, whose interactions with the locals are infused with the folksy levity of a social misfit. By the end of the story, Lester’s unlikely relationship with his local fishing guide reveals the wistful sensitivity that lies beneath Lester’s humor. In ‘The Ketzer,’ the short, terse sentences of the Potts family are fraught with emotional nuance. The longest story in the collection, ‘Luce,’ introduces a diverse cast of characters, including tough kids, tippling housewives, and a giant fish named Adolph. Carpenter’s finesse with human frailty is at its most compelling when he looks at the world through the eyes of a twelve-year-old boy during a summer vacation. The most harrowing story, ‘Turkle,’ renders the harsh Canadian winter a capable and unforgiving opponent to the story’s main character, a tough and stubborn father of three young children.

Carpenter’s characters seek acceptance and connection, no matter how different they may be from one another. In ‘The Ketzer,’ Flora, a young woman in a family of hunting men, strives in vain to be seen: ‘While her brothers talked hunting at the far end of the table, Flora, getting drunk with unaccustomed speed, began to clamour for her father’s attention. He would not even look her way. Then they began to refer to her in the third person and this she could never stand.’

Flora is a typical Carpenter character: someone who desires to be seen as one is, without apologies. This wish propels many of the characters’ choices and underscores a thread of desperation that runs through the stories.

The omnipresent Canadian wilderness; the unexpected pairings of people from different social, cultural, and economic classes; and the eccentricity of characters make this collection a testament to Carpenter’s skill.

Welcome to Canada: Stories will be a pleasure for short story aficionados and for those who respect the beauty and brutality of nature. Elegantly bound with exquisite paper and typesetting, this book is satisfying, profound, and entertaining.

—Monica Carter, ForeWord Reviews

Review quote

‘The latest book by Saskatoon author David Carpenter is a collection of novellas and short stories that succeeds on a number of levels. Welcome to Canada features a landscape that is richly imagined (or perhaps remembered); it is a place where people and nature play an equal role, with the weight of importance shifting smoothly back and forth between them.’

—Carmen Klassen, Saskatoon Star Phoenix

Review quote

‘Spare and often colloquial, Carpenter’s writing invites comparisons with Ernest Hemingway and Thomas McGuane, but his voice is his own. Despite the fact that it is one of the less-travelled areas of our literary landscape, Carpenter Country is a place well worth visiting.’

—Steven Beattie, Quill & Quire

Review quote

‘The characters ring true, and they are characters not always evident in fiction: blue-collar heroes of the backwoods populate the novella ‘‘The Ketzer’’, for example. His milieu is unapologetically, un-ironically Canadian and appropriately titled Welcome to Canada. The book should, by rights, reek of wood smoke. His characters use words like ‘‘hoser’’ and quote from Robert Service, and they appear in stories that are honest, hungry, and muscular, stories that bear-hug the reader with firmness of purpose rather than aggression.’

—Kathryn Carter, Canadian Literature

Author comments

As a kid, I was always aching to get out of the house. The ravine, the playground, the rink, the beach, the bush, anywhere but home. I think these stories of mine are somehow driven by that restless impulse. A trip up north, a football game in a schoolyard, a trek to a secret fishing hole, a drive west. The plots all turn on an outing of some sort, an adventure. I have friends who scarcely ever stray more than 10 metres from a Jane Austen novel. With her narratives, the action is usually inside the house, perhaps a parlour, a ballroom, a drawing room, perhaps a place where one has a conversation over tea. There is a time in a young writer’s life when s/he either goes with that social world (like Fitzgerald did, like Henry James did, like so many English novelists did), or s/he lights out for the territory with Melville and Conrad, or more recently with female writers like Munro and Atwood, because sometimes the protected walls of home can be a stifling place in which to learn about life.

Biographical note

David Carpenter spent his first twenty-three years in Edmonton, working in the mountains during the summers as a car hop, a driver for Brewster Rocky Mountain Grayline, a fish stocker, a trail guide, and a folksinger. He read French and German at the University of Alberta to indifferent effect. He graduated and taught high school in Edmonton until 1965, then migrated south to do an M.A. in English at the University of Oregon. He returned to Canada in 1967 and once again taught school until the summer of 1969, when he enrolled for his Ph.D. at the University of Alberta.

Between 1985 and 1988 Carpenter published a series of novellas and long stories -- Jokes for the Apocalypse, Jewels and God’s Bedfellows. Jokes for the Apocalypse was runner up for the Gerald Lampert Award, and his novella The Ketzer won first prize in the Descant Novella Contest.

In 1997 Carpenter turned to writing full-time. A first full-length novel, Banjo Lessons was published in 1997 and won the City of Edmonton Book Prize. During the early nineties he also finished the last of his personal and literary essays which make up Writing Home, his first collection of nonfiction. The essays explore his engagements with such writers as Richard Ford, Mordecai Richler, the French writer/scientist Georges Bugnet, and the late Raymond Carver. Several of these pieces won prizes for literary journalism and for humour in the Western Magazine Awards. One of these essays was featured in an expanded form on CBC Radio’s ‘Ideas’. He brought out a second book of essays about life around home, a month-by-month salute to the seasons entitled Courting Saskatchewan. It won the Saskatchewan Book Award for nonfiction.

Throughout the years he has always been a passionate outdoorsman and environmentalist. This abiding love of lakes, trails, streams and campsites translates into city life in Saskatoon as well, where he lives with his wife, artist Honor Kever, and their son Will.

Discussion question for Reading Group Guide

1. Carpenter uses voice and colloquialisms to great effect in his stories, and a shift in either of those aspects often signifies an important shift in the story, as well. Do you think that the many voices in Welcome to Canada are authentic or larger than life? What are the implications of your opinion for the collection?

2. Arguably, every protagonist in Welcome to Canada is innocent in one way or another. What role does storytelling play in the construction or deconstruction of innocence? Where is the line drawn between truth and falsehood in Carpenter’s stories?

3. How are the protagonists’ innocence -- and your understanding of the concept -- challenged or reaffirmed by their interaction with nature and the wilderness?

4. In the second-last paragraph of ‘‘This Shot,’’ the narrator remarks that ‘‘Sometimes when I walk past the old house on a summer night I can almost hear my grandfather telling stories of terrible blizzards, problem bears, deer hunts and monster pike ...’’ As reviewer Dave Williamson notes, this ‘‘can be seen as an allusion to most of the topics covered in the stories that precede this one’’. What other allusions or connections did you notice in and between the stories? How do they affect your reading of Welcome to Canada as a whole?

5. How does Carpenter characterize nature and the wilderness? Is nature an object or a subject in these stories? How do individual animal characters fit into the broader Canadian landscape?

6. Welcome to Canada is also described as ‘‘a collection of novellas that dramatize what happens when a character meets his or her opposite.’’ Do you agree? Do personality opposites exist in real life -- or could they? Consider the opposites in each story: who are they? How do opposites interact?

7. Why do you think David Carpenter titled his collection Welcome to Canada? Is Carpenter’s Canada a familiar one or does it challenge convention? Could these stories have been set elsewhere? Who is being welcomed to the country?

8. How does the cover of the book affect your interpretation of the stories? Does it accurately reflect Canada or Carpenter’s themes?

9. Carpenter’s writing has been described as very masculine, but are his themes and stories? How do female characters -- animal and human -- interact with Carpenter’s masculine world? (And is it a masculine world?)

10. Most of the stories in Welcome to Canada are told from a removed perspective; the narrator is remembering a story or memory from long ago. What is the relationship between memory and storytelling? Memoir and storytelling? The wilderness and storytelling? How do these individuals’ memories welcome one to Canada?

Introduction or preface

Right from the beginning of his fiction-writing career, David Carpenter has been a master of voice and character. Those plucky Jewish footballers in ‘Protection’, his first published story, have stayed with me ever since I first made their acquaintance more than twenty-five years ago. Theirs was a world I knew virtually nothing about at the time, yet their voices in the story were so vigorous, so pugilistically and poetically authentic, that I believed in them wholeheartedly and wished that I could be welcomed among them, like the story’s narrator Drew. I was just beginning my own experiments with fiction writing at the time (under the extraordinarily patient guidance of one D. C. Carpenter), and I remember reading that story over and over again, trying to understand the trick of how he brought those boys so vibrantly to life in such a short space.

I never did entirely figure out Carpenter’s secret, though I knew it had something to do with his remarkable memory for accents, dialects and colloquial turns of phrase. As I’ve read his many works of fiction in subsequent years, I have never ceased to be amazed at his talent for rendering voices onto the page. His characters don’t simply speak; they pronounce themselves into being. He is preternaturally attuned to the poetry of the vernacular and the extraordinary variety of Canadian English, and he is able to place each of his characters in their own particular spots on that lavish linguistic spectrum, so that every phrase they speak contains a compendium of information about where they come from, what they want out of life, their successes and failures. To render dialect in this manner, without it becoming ironic or distracting -- without losing the reader’s empathy for the characters -- is an extremely difficult thing to do. David Carpenter is among that rare company of writers who can seemingly effortlessly transform a few black marks on a page into vital, quirky, utterly memorable people who live on in readers’ memories just like the most interesting of their flesh-and-blood counterparts sometimes do. This ability is enough to inspire a twinge of jealousy in even the most saintly of fellow scribes.

I suppose on a fundamental level, David Carpenter’s secret is simply that he loves meeting people and he takes great pleasure in learning about lives that are different from his own. He is the rarest type of raconteur: he actually does more listening than talking when he finds himself (as he so often does) in a social situation, and he knows how to encourage the best stories out of the many people he meets. A storytelling enabler, one might call him. A catalyst of volubility. His genuine fascination with other people’s points of view is infectious; it empowers people to believe that even their own narratives are worth sharing. And this sensibility is also abundantly visible in the empathy he shows for his characters, even the meanest among them. He is fundamentally a sociable writer, entirely different from the garret-bound recluses and the celebrity-seeking egomaniacs who are much more common in the trade. His stories are conversations with the world, wonderfully vivid attempts to coax us all into the transformative experience of actually listening to one another. In an age that is moving further and further toward the politics of divisiveness and the isolation of individuals, we need Carpenter’s kind of sociable fiction more than ever: fiction that reaches out to readers, welcomes us in, and shows us how closely we are connected to those around us.

No one could mistake Carpenterian sociability for mere chit-chat or neighbourly banter, however. His vision of human interactions is fundamentally ethical and political in nature, and this is partly because his work is so finely attuned to nuances of character. Sociability in his fiction extends across the boundaries of class and age and cultural background, so that each story becomes an unstable meeting-place, a zone of unaccustomed interaction. This is also the source of so much drama in his writing. He brings together people from social strata that are usually separated, and he explores what happens when those social boundaries disappear and people are forced, by circumstances, to get to know each other. Thus in the title story of this volume, he presents us with a rich American tourist awkwardly befriending his Native fishing guide, and in ‘Meeting Cute at the Anger Motel’ he portrays an unlikely meeting between a middle-class couple and a pair of prodigal drifters. Nearly every story in this collection centres on similarly surprising interactions. In ‘The Snow Fence’ there is the unusual relationship between the Cree Muskwa family and the narrator’s white middle class family, and in ‘Luce’ the summer cottage provides a kind of social experiment in which Drew interacts with the tony Bothwell crowd as well as the working-class Bullmer boys and the Aboriginal fisherman Amos Whitehawk. Sometimes the result of such interactions is comic, but there is always a sense of incipient danger too, because the stakes are magnified in situations like this, where different worlds bump against each other. The friction of such contact breaks open people’s lives a little, and sometimes frees them from the bounds they had become accustomed to, but this possibility is always attended by risk and pain as well. And these stories suggest that one of the only reliable solaces for such pain is the company of one another.

Such is the nature of Carpenter’s Canada. It’s a place where boundaries gradually (or suddenly) break down, until people who have very little in common end up depending on one another for their survival. It’s a land of sweet, charming losers and uptight, pitiable winners, a place where adults have no more answers than children do, and where people often play roles in metaphysical struggles far beyond their immediate understanding. In many respects it is a roiling cauldron of contradictions, threatening to boil over into mutiny or anarchy or violent oppression. But something -- some tenuous thread -- pulls in the other direction, toward a generalized community feeling, a sense that differences need not divide people but might instead provide an opportunity for them to learn from each other. We’ve got ourselves into something of a mess here, each story seems to say. Now how are we going to get ourselves out? ‘We’ is the operative word in Carpenter country, and not the royal we, either. We as in welcome.

Wilderness is also a crucial part of Carpenter’s vision. One might say that the sociability of his fiction extends beyond the human sphere and into the natural world as well, inviting us to examine more deeply the ways in which we are all connected to the ecosystems that surround and support us. The animals in these stories -- a mythically huge buck called Appletree, a behemoth northern pike named Adolph, the Coca-cola-sipping bears of ‘The Snow Fence’ -- are as important and as complexly drawn as their human counterparts, and by their silent presence they raise powerful questions about what humans are doing to the world. Humans are obsessive boundary-makers in these stories, not only drawing lines of social hierarchy among themselves but also repeatedly marking a dividing line between ‘civilization’ and wilderness, such as the flimsy snow fence that is erected to separate the bears from the tourists in the national park. Animals live by entirely different rules, and often they suffer for crossing human boundaries that make no sense to them, boundaries that exist only to bolster a particular power relationship that legitimizes human exploitation of the earth. However, there are a few human characters in these stories, such as Flora in ‘The Ketzer’ and Delphine Muskwa in ‘The Snow Fence’, who recognize that the natural world is not a savage wilderness to be plundered or walled out, but is in fact the dwindling repository of a particular kind of nonhuman wisdom that will some day be needed if we are to have any chance of saving the world from ourselves.

And that is what these stories are ultimately about: the small but lingering possibility of redemption for this tragically messed-up world and its remarkably flawed inhabitants. Carpenter doesn’t harbour illusions about the redemptive capacity of his characters, or of the human species in general, but at the same time he refuses to give in to despair or cynicism or empty self-absorption. His stories are beautifully honed acts of generosity. Reading each one is like happening upon an unexpected gift. We return from Carpenter country with a new appreciation for the people and creatures of our own everyday countries, especially the ones we have all too often ignored.

—Warren Cariou, University of Manitoba

David Carpenter spent his first twenty-three years in Edmonton, working during the summers as a car hop, a driver for Brewster Rocky Mountain Grayline, a fish stocker, a trail guide, and a folksinger. He read French and German at the University of Alberta to indifferent effect. He graduated and taught high school in Edmonton until 1965, then migrated south to do an M.A. in English at the University of Oregon. He returned to Canada in 1967 and once again taught school until the summer of 1969, when he enrolled for his Ph. D. at the University of Alberta.

Between 1985 and 1988 Carpenter published a series of novellas and long stories -- Jokes for the Apocalypse, Jewels and God’s Bedfellows. Jokes for the Apocalypse was runner up for the Gerald Lampert Award, and his novella The Ketzer won first prize in the Descant Novella Contest.

In 1997 Carpenter turned to writing full-time. A first novel, Banjo Lessons was published in 1997 and won the City of Edmonton Book Prize. During the early nineties he also finished the last of his personal and literary essays which make up Writing Home, his first collection of nonfiction. The essays explore his engagements with such writers as Richard Ford, the French writer/scientist Georges Bugnet, and the late Raymond Carver. Several of these pieces won prizes for literary journalism and for humour in the Western Magazine Awards. One of these essays was featured on CBC Radio’s ‘Ideas’. He brought out a second book of essays about life around home, a month-by-month salute to the seasons entitled Courting Saskatchewan. It won the Saskatchewan Book Award for nonfiction.

Throughout the years he has always been a passionate outdoorsman and environmentalist. This abiding love of lakes, trails, streams and campsites translates into city life in Saskatoon as well, where he lives with his wife, artist Honor Kever, and their son Will.

For more information please visit the Author’s website »

The Porcupine's Quill would like to acknowledge the support of the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. The financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) is also gratefully acknowledged.