The Porcupine's Quill

Celebrating forty years on the Main Street

of Erin Village, Wellington County

BOOKS IN PRINT

Joyce Wieland by Jane Lind

A look at the early aspirations and fears of a young woman who would become the renowned Canadian artist Joyce Wieland. A very fascinating personal story unfolds in a series of diaries, kalideiscopic streams-of-consciousness and sketches, of a self-developing individuality and of the philosophical literacy of one of Canada’s great artistic innovators.

Joyce Wieland (1930-1998) is legendary for her contribution to the development of contemporary visual arts in Canada. A self-described ‘cultural activist’ she is best known for celebrating Canadian national identity and bringing forward feminist issues within the predominantly male art culture of the time. Initially a painter and filmmaker, she also embraced traditional women’s media such as quilts and sewn collages. In her mind, the landscape and ecology of Canada was female. Issues of gender and nationality were interchangeable. Concern with the protection of Canadian confederation and gender issues would repeatedly surface in her quilts, films and assemblages.

Wieland was left in the care of an older sister after the death of both of her parents. She took solace in drawing and creating comic strips. During her high-school years, she was encouraged to enroll in the visual art program. Later, work as a graphic designer and at an animation house provided her with techniques that would be used in future art production. In 1956, Wieland married the artist Michael Snow. Two years later, she had her first solo show and, by 1961, she was represented by Toronto’s leading art dealer, Avrom Isaacs, of the Isaacs Gallery.

Wieland then immersed herself in the New York art scene, relocating there with Snow in 1962. She turned to the underground filmmaking community. Most of her own films were made during her stay in the city and shown at local festivals.

Many of Wieland’s ideas, including nationalism and feminism were formulated in New York during this time away from Canada. Cooling Room II (1964) shows the influence of American pop culture and filmmaking on her work. Alongside a toy airplane and an image of a sinking ship, a heart cut out of red material hangs to dry on a clothesline. A series of coffee cups with lipstick stains mark the passage of time. The predominance of red and white suggest an equation between heartbreak, disaster and the colours of the Canadian flag. Confedspread (1967), playfully composed of numerous sewn squares of colorful plastic and synthetic fillers, is Wieland’s first attempt at using the quilt format as a vehicle of expression.

More quilts would follow: Reason Over Passion (1968) echoed the words of Pierre Trudeau. Her retrospective at the National Gallery in 1971 was its first ever for a living woman artist. In it, she introduced ideas of artistic collaboration to the public by contracting groups of sewers to help create the quilts.

Joyce Wieland’s prolific career lasted over thirty years and established her as an icon of Canadian art history. She is credited with introducing ideas and breaking conventions that contributed significantly to the development of contemporary art in Canada.

2011—ForeWord Magazine Book of the Year,

Shortlisted

2011—Alcuin Award for Excellence in Book Design,

Commended

Table of contents

Preface

Joyce Wieland -- A Personal History

Introduction to the Selections

Selected Writings and Drawings

Toronto Journal 1952-1955

France Journal 1956

Explorations in Words and Drawings 1956-1962

Profiles of Family and Friends 1958-1961

‘Hip Hip Hooray: We’re Living in the U.S.A.’ New York 1962-1971

Notes

Credits

Review text

In Joyce Wieland: Writings and Drawings, editor Jane Lind curates a collection of journals and sketches, granting readers a multi-dimensional look at the life of Canadian artist Joyce Wieland. Wieland, born into a ‘rough-and-tumble’ life in Toronto, wrote of her complicated circumstances in her diaries, scribing decades of love, art, and travel. Driven by her two disparate desires -- to marry and to make a name for herself as an artist -- Wieland often captures the tensions between these pursuits in both her writing and drawings. In one entry, while living in France, Wieland decreed in her journal ‘... I must before the time passes, show in my work, what it is to love ... to show in my work how glad and good and magical it is to live and feel, smell, think, etc.’ In her imperfect grammar, her raw and declarative prose, we read of her sweeping desires to effect change through art -- change which certainly shaped, according to Lind, the Canadian contemporary art scene.

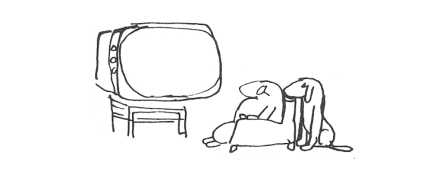

Accompanying Wieland’s written thoughts and stories are her drawings, some in color and some black-and-white. The sketches, mostly of people and animals, are both whimsical and serious, adding spirit and dimension to the diary entries. Here, we see talking bespectacled dogs and disembodied phalluses; we find artists painting to a crowd and barely discernible sweeping lines in the shape of a woman’s torso. Lind also includes several short narrative sketches, showing Wieland’s storytelling range. Intimate and detailed, these sketches help illustrate the private life of Wieland, her thoughts and fears about making art: in one drawing, a ‘New ‘‘Old Master’’ Machine’ paints a masterpiece, with the artist holding its buttons and levers. This echoes a written phrase of Wieland’s from early in her career: ‘Although Im [sic] making a little money with my art Im not doing any serious work -- which bothers me.’

Together, the entries and the drawings create a complete picture, a complex and multi-faceted portrait of an artist preoccupied with the meanings of making art and finding love. Lind has done a super job of culling all sorts of compelling multimedia, including -- at the collection’s end -- facsimiles of Wieland’s poetry. In this way, the reader is able to see the artist even more clearly, through the dips and curls of her handwriting. Readers intrigued by the interworkings of an artist’s inner realm -- the private life of the public figure -- will certainly find much of interest in this well-shaped collection.

—Rachel Mennies, ForeWord Reviews

Review quote

‘Joyce Wieland: Writings and Drawings provided an eclectic mixture of drawings, journal entries, poetry and other writings that span nearly two decades. This book was admittedly a fun and interesting introduction to a rather quirky artist/writer with whom I was not previously familiar.’

—Bytown Bookshop

Review quote

‘Joyce Wieland is a fascinating read that is sure to give greater appreciation of this famed Canadian artist.’

—Margaret Lane, Midwest Book Review

Biographical note

Joyce Wieland (1930-1998) was an artist who, during her career of nearly forty years, broke down many barriers women faced in a male-dominated art world. As part of her strong survival instinct, she developed a sharp wit and acute ability to find the dramatic aspects of life with their humorous incongruities. She translated what she saw into visual images and words, revealing her own unique way of seeing.

Wieland worked in whatever medium and genre she required to articulate what she wanted to say: drawing, painting, collage, multimedia constructions, fabric works, experimental films, cartoons, words. Her cartoons and writing -- playing with language -- are not so well known but must be included in a list of her media. Throughout her life she wrote sporadically; she was most consistent at keeping a journal during blocks of time in her youth. She jotted down her thoughts about art, wrote profiles of people she knew, and tried stream-of-consciousness poems.

Wieland came into adulthood during an era of our history that was extremely repressive, especially for women. All of her work is grounded in her experience as a woman and her personal vision as a Canadian. That the subject of some of her earliest work was explicitly sexual is somewhat astounding, given that she began working as an artist in the 1950s when generally only male artists were ‘privileged’ to draw and paint nudes. Regardless of the medium she chose to express herself, from the beginning, her origins fed her process of making art.

Wieland grew up in a rough-and-tumble atmosphere. Her father was part of a long line of British pantomime performers who played in the music halls and theatres of London -- including Theatre Royal, Drury Lane -- as early as 1839. George Wieland, Joyce’s great grandfather was a famous nimble clown, unequaled in his time. Two of her great aunts, Clara and Zaeo, who gave Joyce a sense of family pride, were well-known dancers who also performed circus acts.

In her mother’s family, the Coopers, Joyce also found a role model, her grandmother. Mary Jane Cooper Watson was an independent woman who opened a sweet shop after her husband, Charles Watson, deserted the family. Their home was in the small hamlet of Cotton Mill north of Nottingham, England where lace making was the dominant industry. Joyce claimed her grandmother as her personal inheritance for that independent spirit, just as she claimed her paternal great aunts for their daring.

Joyce’s mother, Rosetta Amelia, was a feisty girl nicknamed Billy when she was young, probably because she developed a reputation as a tomboy. When she was a teenager, she left home and went off to London where she met Sidney Wieland and fell in love with him. The two began living together even though Sidney had another wife and two children.

In 1925, Sidney Wieland, Joyce’s father, left England for New York. The next year he sent for Joyce’s mother, who left behind in England their two children, six-year-old Sidney and five-year-old Joan, in the care of acquaintances. By the next year, Sidney and Billy were living in Toronto. When they received a letter from friends saying the children were being mistreated, they sent the money for their fare, and their friends sent them to Canada by ship.

The birth of Joyce in 1930 in Toronto was the family ‘accident’ at the beginning of one of the worst decades in the city’s history. They lived in a tiny house on Claremont Street in a working-class Toronto neighbourhood of immigrants near Bathurst and Queen Streets.

Though Sidney worked as a waiter at the largest hotel in the British empire, the Royal York, he could barely support his family on his meagre earnings. He was among the many who stole food in desperation during the Depression years; it was easy for him to pilfer meats and pastries from the hotel to supplement buying groceries. Billy did what she could, looking after the house, cooking, and sewing for the family. An accomplice with Sidney, she stitched pockets to the inside of his coat where he could hide whatever he chose to bring home, one pocket that was even big enough to hold a whole chicken. In the midst of the family poverty, Joyce discovered very quickly that she was her father’s favourite; he indulged her by allowing her to eat what she wanted and do as she pleased.

Sidney Wieland’s cunning, coupled with his wit, served him well in a struggle for survival. Despite his best efforts, he did not stave off the feeling of deprivation in the household, and things became even worse for Billy and the three children when Sidney died of heart disease in 1937. He left behind a family with little means of support. Billy made rag rugs to sell; Joan and the younger Sidney had to find jobs.

The three Wieland children were orphaned four years later when Billy died of bowel cancer. Joan, at age nineteen, took responsibility for her younger sister, nearly eleven years old. However, Sidney joined the army and was absent during the years immediately following their mother’s death.

The poverty of Joyce’s early years continued throughout her adolescence, a Dickensian existence that haunted her most of her life; she never did shake off her fear of deprivation. By the time Joyce reached adolescence and began thinking about the future, the outlook for her, a very poor working-class girl, was bleak. What would she do after high school? Joan, still her sister’s guardian, knew Joyce would have been a disaster as an office worker and enrolled her in the art program at Toronto’s Central Technical School. There, her artistic abilities became obvious to one of her teachers, Doris McCarthy.

One day McCarthy told her young student she had the potential to become an artist. Until then, Wieland had no idea that a career as an artist even existed, despite that earlier in her life she had felt drawn to art. At age thirteen, she had written in her diary that she ‘saw the most wonderful art today it ws (sic) marvelous I am happy go lucky wacky...’. And later, another day, she recorded that she ‘painted some great masterpieces to day.’

Soon after Wieland graduated from high school in 1948, she found a job designing packaging for a company called E.S. & A. Robinson, a job she kept for nearly five years. During those years she began taking seriously her desire to become an artist and at the same time, she had her first serious romantic relationship with a young man who was typical of the era -- he did not think Joyce could travel and make art and still be a good wife. This young man’s attitude felt like a threat to her passion for her art and threw Joyce into a period of inner turmoil because it seemed she had to choose between two life prospects that were equally important to her: marriage and making art. The relationship ended when Joyce realized she would not want to marry this man.

At age nineteen she rented her own studio, an expense she could take on, given that her other costs were not high as she was living with the family of her friend Mary Karch. Two years later she moved into her studio and began living on her own, an unusual step for a young woman in 1951, especially since the other occupants of the house were men, and ‘wild’ artists at that. She became friends with them, the beginning of her life in a circle of artists.

During the early to mid fifties, choices Wieland made firmed up her commitment to being an artist. She took a job at Graphic Associates where she met other artists, including Michael Snow whom she married in 1956. Along with a few other artists, Wieland and Snow began making experimental films. Wieland was also painting, and began a series of lovers drawings, which she continued into the early sixties.

At that time, the centre for showing contemporary art in Toronto was the Isaacs Gallery whose artists were nearly all men. These male artists, typical of their time, related to women not as artists but as sexual partners who cooked dinner and made coffee. Wieland, however, broke out of the stereotypical mold. She showed her work at the Isaacs Gallery, where she held her own in a chauvinistic atmosphere.

For the Toronto artists, New York held an allure -- in their minds that was where everything important was happening. From time to time Joyce and Michael talked of going to New York. In late 1962, they left Toronto and in early 1963 found a loft in Manhattan and moved in. Here they made friends with film makers; the world of experimental film became a big part of their life. At the same time, Wieland continued experimenting with a variety of other media that included plastics and fabric. It was while she was living in New York that she began channeling her fervent love for Canada into her art works.

In 1969, Pierre Théberge, then the Curator of Contemporary Art at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, offered Joyce a show of her work. ‘True Patriot Love -- Joyce Wieland -- Véritable amour patriotique,’ opened in 1971, a landmark in Canadian art because it was the first solo exhibition by a living female artist at the National Gallery. That was also a pivotal year for Joyce and Michael, personally -- they returned to Toronto to live, bought a house and settled into life in the city.

By then Joyce had developed an idea for a feature film, based loosely on the Canadian artist, Tom Thomson. She gave over her life to making The Far Shore during the first half of the 1970s. Increasingly, Wieland and Snow experienced stress in their relationship and when it became obvious that Snow was committed to his mistress, Wieland left in 1979 and began living alone in a little house on Queen Street that she and Snow had purchased when she was working on The Far Shore.

For Wieland, the break-up of her marriage was fraught with the trauma of childhood abandonment. She attempted to heal herself through her art and launched into a series of coloured-pencil drawings, which she showed at the Isaacs Gallery in 1981, an exhibition called The Bloom of Matter. Subsequently she returned primarily to painting, including many large canvases.

By the mid eighties she had built up a new body of work and in 1987 she claimed another honour: she became the first living Canadian woman to launch a major retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario. As she worked on preparations for this exhibition, she had difficulty focusing on the necessary organization required for a retrospective, and the management of her life in general had become overwhelming, even with the help of assistants.

By the late eighties and early nineties Wieland knew something was wrong; her friends, colleagues and assistants also realized she was ill. Her diagnosis was Alzheimer’s Disease. Her subsequent deterioration and death in 1998 left a void in Canada’s art world.

Introduction or preface

For her thirteenth birthday at the end of June 1943, Joyce Wieland received a diary as a gift. Until December of that year, she wrote consistently in the diary, her earliest writing extant. In these entries, always beginning with ‘Dear Diary,’ she noted the weather, arguments, guests, and visits she made to friends. The highlights of her life during those five months were attending movies (twenty references to having seen films), occasionally getting new clothes and special treats -- fish and chips and cake. She also mentioned letters to and from her older brother Sidney, who was overseas until the war ended.

Nearly eight years after that first diary, in 1951 Wieland began what she called ‘Private Notes and Philosophical Jottings’ in a black fifty-cent notebook. The section in this collection, ‘Toronto Journal 1952-1955,’ is made up of selections from this notebook. Here she wrote about her social life, her desire for love, along with her confusion about her feelings for men. She loved Brian Barney, an aspiring writer who introduced her to great literature, with whom she lived for a few years. His company was a pleasure to her as the two of them talked of literature and life, and took long walks looking for book sales. In this journal we learn about Wieland’s reading: André Malraux, Malcolm Cowley, and Colette. Colette was a writer whose life and books Wieland particularly admired; she talked endlessly to her friends about Colette.

‘Private Notes and Philosophical Jottings’ shows clearly the conflict arising from Wieland’s own desires and the typical societal expectations of that era in which a young woman was expected to marry and to give over her life to her husband and children. We can sense a progressive building of emotional intensity in her journal as she moves through her friendships, leaves Barney behind, falls in love with Michael Snow, and begins a relationship with him.

Wieland wrote frequently of her two strong desires: marriage and making art. Sometimes the search for a suitable man took priority; other times she felt convinced she wanted only a career in art. She lived out much of her life in the early fifties inside the dichotomy of these two options. That Wieland could not stifle the passion for her art becomes clear by the end of this journal in 1955 as she looked for ways of harmonizing the two parts of her life she cared about the most.

‘France Journal 1956,’ was written the spring after Wieland fled Toronto for France, thinking that putting physical distance between herself and Snow might be one way of discovering whether he was serious about her. Life on the other side of the Atlantic cast her Toronto friends in a different light; she eagerly awaited their letters as she became wistful about home. ‘I am very patriotic about Canada now,’ she wrote.

Wieland entered wholeheartedly into her experiences in France, even if she missed her homeland. Her journal gives us a picture of her interactions and experiences with new friends and her drawing, painting, and reading. She expanded the literary explorations she began when she lived with Bryan Barney: Franz Kafka, Katherine Mansfield, Simone de Beauvoir, Marcel Proust and Anton Chekhov. A few times Wieland wrote of her impressions in looking at art, and, as in the Toronto journal, she describes her friends and her feelings about them, her likes and dislikes, all the while revealing her distinct sense of humour.

Living in a new environment was conducive to contemplation and formulating her ideas about her own work and art in general. The work of the artist, she concluded, was to give voice to whatever was within. At that time she voiced her thoughts on expressing love: ‘I must before time passes show in my work what it is to love,’ she wrote. Her lover drawings were her attempt at doing just that.

‘Explorations in Words and Drawings 1956-1962’ is a selection of poems and sketches, early lover drawings and cartoons. In some of these writings, Wieland expresses similar ideas as those in her journals. Her reading in the early fifties, her explorations of authors while she was in France, nourished her experimentation with language.

In most cases Wieland did not bother affixing a title to these word sketches; they simply started and stopped. The longest one, ‘I am in Paris,’ begins with an incident from her first visit to Paris in 1953 with her friend Mary Karch. Memories of events that occurred along the Seine move into impressions and free associations with her experiences there.

Other selections in this section are more cryptic and, at the same time, energetically expressive. Wieland uses symbolism in a way that is somewhat mysterious. She excels at satire as she writes about critics, museum women’s committees who like to think they are doing artists a favour, and businessmen of Canada.

Chickens -- caged fowl -- are a part of the story that concludes her France journal, and chickens appear again in her drawings as characters through whom Wieland conveys her love of satire and her sense of humour. She expresses so eloquently her feelings about politicians, something she hinted at toward the end of her France journal when she wrote that politicians would be better off going down the street to ‘help out old man Jones’’than doing whatever it is they usually do.

It was the ‘lover girl,’ however, who became the central part of the story, the author of the word sketches about love and the drawings. We need to look at the lover drawings in the context of the time in which Wieland was working. In the 1950s women simply did not ‘do’ this kind of work about sexuality. The female figure was the prerogative of men, but in these drawings of male and female bodies, Wieland transgressed the terrain of the male artist. Then she went further, to draw disembodied limbs, genitalia, breasts, and a deluge of sperm covering the pages.

Sex, politics and religion are the subjects that are most vested with emotion. Wieland used all three in her sketches. There is nothing that is sacred or taboo in her reservoir of ideas. God the Father Divine is drawn with a penis stuffing his mouth. According to her, even the ‘holiest’ of males, God the Father Divine, enjoys a disembodied woman’s open legs.

There it is. Politics, sex, and religion, according to Joyce Wieland.

‘Profiles of Family and Friends’ takes us to Wieland’s beginnings in her family, and her friends as a young adult. She tells the story of her birth, and in each attempt she includes different details that may or may not have occurred; these are fanciful writings packed with nostalgia. And part of the nostalgia is embedded in the details: picturing her mother smoking ‘turret cigarettes’; wanting to see a photo of her mother in a ‘leghorn hat,’ a hat of finely braided straw; reflecting on her love for the Canadian countryside as she sat on trains riding around Europe!

The ‘she’ in some of her stories is certainly herself, and the variously named other characters are her friends whose names are not those she uses.

Her character sketches penetrate the inner terrain of her friends with a sharp perception and wit that might prove embarrassing if she had identified them. She used only a single initial for each one in the section that begins ‘you can’t rent what you own,’ whether or not that was intended as the title, but that is the line preceding all these character sketches on the page.

Wieland invents words as she needs them, for example ‘a warm zoftinkness.’ She used her journal and other notes to work out what she wanted to say and how she wanted to say it. Sometimes she wrote several versions of the same entries; I usually selected what seemed to be her final version.

‘Hip Hip Hooray: We’re Living in the U S A’ is a selection from Wieland’s sketch books and drawings on loose pages from the years she lived in New York City. Her focus here shifted from drawings of lovers to thinking about art and artists, and many of these sketches reflect her questioning of the way things work in the art world. Her free-flowing approach in her thinking and in her work becomes apparent in her pages of lists. ‘Making a list isnt (sic) making a poem,’ she wrote. But she makes lists regardless.

Wieland’s place in a circle of experimental film makers was an integral part of her life in New York. Some of the drawings in this section reflect her work in film -- she worked on a number of films during the 1960s.

Some of the selections show that Wieland delighted in poking fun at art and artists, as well as art history. A peculiar apparatus appears in ‘The New ‘‘Old Master’’ Machine Perfected and Demonstrated January 19, 1964,’ a machine that paints a nude by squirting materials from spouts labeled ‘hair,’ ‘lace’ ‘space.’ This performance takes place in front of a crowd of people, both men and women. On the same theme, another cartoon features an inflatable kit to create a blow-up of a voluptuous nude. This cartoon demands that we think about the place of the female nude in painting, and how women have been treated throughout the history of art.

‘Machine strangles man / machine turns man into the work of art,’ reads the heading of another cartoon. Wieland is exploring how to talk about the workings of the art world because another cartoon reads ‘Art is Fun,’ and yet another, ‘Art is Long / Life is Short.’ Is she telling us that the ‘machine’ of the art establishment can strangle? The art world in New York was a male stronghold, and Wieland avoided it -- she did not show her work there, but continued showing in the Isaacs Gallery in Toronto.

On Wieland’s page headed by her type-set name misspelled (‘Weiland’), she created her own sayings and also used common cliches to dismantle the reverence of the faithful in the religion of art: ‘heaven is only for the pure in art’; ‘Thou shalt not have thy cake, but only art hereafter’ ‘home is where the art is!!’ Wieland herself is included in these cartoons in which she satirizes art, for she herself was convinced of the importance of art, that art is love. It would not be wrong to say that for her art was religion.

Living in New York stimulated Wieland’s thinking and her creative work; she used a variety of media to express her thinking. How women were barred from the art world, how men attempted to relegate women to a lower status, became clear to her in New York. She could not accept being categorized in that way, and courageously used her own experiences as a young woman to fuel her determination to create a place for herself. She is remembered not only for her work, but for the trail she blazed for the succeeding generations of female artists in painting as well as in film making.

—Jane Lind

From the early seventies until the mid nineties, Jane Lind worked as a freelance book editor and writer in Toronto. For many years she also worked as a sculptor, exhibiting her work in public and private galleries in Toronto and southern Ontario. Since 2001, she has been researching and writing a biography of Russian-born Toronto artist, Paraskeva Clark (1898-1986) who was trained in St. Petersburg in the early 1920s. Clark had some influence among Toronto artists during the thirties and forties because of her strong belief that artists should use social issues as their subject matter. Perfect Red: The Life of Paraskeva Clark was published by Cormorant Books in 2009. Currently Jane Lind lives in a rural area of Wellington County, near Guelph, Ontario.

The Porcupine's Quill would like to acknowledge the support of the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. The financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) is also gratefully acknowledged.