The Porcupine's Quill

Celebrating forty years on the Main Street

of Erin Village, Wellington County

BOOKS IN PRINT

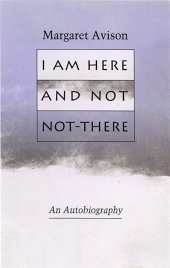

I Am Here and Not Not-There by Margaret Avison

‘Margaret Avison was a highly regarded Canadian poet who saw poetry as her life’s vocation but shied away from being publicly labelled a poet. She has been called reclusive, introspective; her poetry difficult and demanding. And yet, as shown by her enigmatically titled autobiography, I am Here and Not Not-There, she was also a woman with a lively curiosity and a real love for the world.’

This question was put by a registrant: ‘What makes a poet’s language distinctive?’ We all fell silent, trying to pin it down, then tried to answer. Not just affection for words, which is common to all good writers; not necessarily a matter of cadence, formal structures, rhythm. The answer that came to me, forced out of minutes of dismissing options, was new to me too: ‘It is saying ‘‘I am here and not not-there’’.’

2010—Independent Publisher (IPPY) awards,

Runner-up

Table of contents

Preface

Autobiography

Beginning?

Early Childhood

Calgary

Toronto

Student Years

Short-term Jobs

Jobs on Campus

Escaping a Career

Academia

Evangel Hall

London, Ontario

CBC Archives

Mustard Seed Mission

Mother’s Death and After

Poets Learn From Poets

Documents

Cars

Space

Vanity

Coming to Terms With Tolstoy

Miriam Waddington

Letter to Miriam Waddington

Letter to Miriam Waddington

Letter to F.R. Scott

Letter to Miriam Waddington

Letter to Cid Corman

Letter to Cid Corman

Letter to Miriam Waddington

Letter to Eleanor Graham

Letter to Eleanor Graham

Letter to Miriam Waddington

Poetry and the Doukhobors

Dependent/Dependant

There are several writers-in-residence

Governor General’s Awards 1990

Interview with Cristina Cassanmagnago

Ray Souster and the Contact Years

Putting Computers in Perspective

Clothes

Interview with Sally Ito

Letter to Burton Hatlen

A Conversation With Margaret Avison

On Xmas

Slow Breathing

Margaret Avison: Significant Dates

Review text

To the question, ‘What makes a poet’s language distinctive?’ Avison once ad-libbed, ‘Not just affection for words, which is common to all good writers; not necessarily a matter of cadence, formal structures, rhythm ... [but the realization] I am here and not not-there.’ This attention to word and story, delivered with a pleasing humility, permeates Avison’s life story, I Am Here and Not Not-There. Avison died before finishing the book; her close friend and assistant, Joan Eichner, with editor Stan Dragland, completed the project, adding an appendix of essays, letters, and interviews. The result is an intimate portrait of one of Canada’s most beloved and well-known poets.

A minister’s daughter, Avison was brought up to be kind. Her grandmother told her, ‘You can learn something from everybody, something to do, or something not to do.’ She suffered a teenage bout of anorexia nervosa and peer-group smoking and drinking, but later devoted her life to church missions and caring for her blind mother. She became an educated professor, but her primary identity was that of a poet.

Avison’s autobiography is filled with anecdotes about her poetry, day-to-day events, and people with whom she came in contact. She details childhood memories with an adult’s perspective; her topics range from family holidays in the snowy countryside to walking through interesting neighborhoods while living in Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Toronto, and Ottawa. She writes about both World Wars, the Great Depression of the 1930s, and her ongoing education -- a B.A., M.A. and all courses for a doctorate -- as well as her clerical, teaching, and editing jobs. She even visited France as a nanny. The poems based on these experiences, each written honestly and with the skill of a master, won her Canada’s literary honors and affection.

That affection was returned: Avison loved her home. In 1956, Avison won a Guggenheim Foundation Grant that took her to Chicago, where she organized decades of her poetry. She responded in amazement when her new friends suggested she become a U. S. citizen: ‘But I want to be back in Canada!’

The poet continued to follow early advice to eliminate the first person singular pronoun, and this characteristic humility remained a core part of Avison’s identity even as she received publishing honors: two Governor-General’s Awards, the Griffin Poetry Prize, and the Canadian Authors Association’s Jack Chalmers Award. In 2005, she accepted the Leslie K. Tarr Award for her prestigious Christian writing in Canada. Her most prestigious books include Winter Sun, sunblue, and No Time.

This is an enjoyable and educational autobiography of an accomplished artist, and a model for not only poets, but teachers and others dedicated to serving humankind.

—Mary Popham, ForeWord Reviews

Review quote

‘This week I received a large package in the mail. I opened it to find the 352-page volume I Am Here And Not Not-There: An Autobiography. It is the autobiography of Margaret Avison -- the exceptional Canadian poet who passed away on July 31, 2007. Not only is Margaret Avison one of the most celebrated poets Canada has ever had -- having won the Governor General’s Award for poetry in 1960 and 1990, and the Griffin Poetry Prize in 2003 -- but she participated with The Word Guild by twice contributing to the Write! Toronto conference, and by being the winner of the Leslie K. Tarr Career Achievement Award in 2005. I am not writing of this book, so much, to encourage you to buy it -- unless you are a long-time fan of Avison -- but primarily to point out the weight of her contribution. Sarah Klassen once wrote in Prairie Fire, ‘‘It is Avison’s unique accomplishment to write, in and for a secular world, about faith and God, with intelligence and without becoming either sentimental or preachy.’’ Surprisingly, it is the secular literary community -- not the church -- that has most valued Avison’s legacy. I think it’s high time that we begin to celebrate Margaret Avison!’

—D. S. Martin, twgauthors.blogspot.com

Review quote

‘A high-school teacher once told a young Margaret Avison to eschew the first person singular in her writing for 10 years. It was a directive the naturally withdrawn Avison readily took to heart. Nevertheless, the quintessential Canadian literary question is Alice Munro’s: ‘‘Who do you think you are?’’ It is a question an older Avison consistently demands of herself in this posthumously published autobiography.’

—Zachariah Wells, Quill & Quire

Review quote

‘A consummate perfectionist who savoured every word, delighted in twisting and extending its conceptual sinews, purified its cadence, and plumbed its deepest interiority, Avison fought with words in the same way you would wrestle with an angel. Her startling images drawn from nature and technology left one in no doubt that a greater wisdom than knowledge is lost to those whose gods of efficiency, calculation, technical mastery, and data assembly deafen them to the sounds and furies of the natural world, blind them to the beauties of ordinary epiphanies, and dull that imagination that brings us close to Divinity.’

—Michael Higgins, Saint John Telegraph-Journal

Review quote

‘In editing the unfinished manuscript of Avison’s autobiography and reissuing her 1993 Pascal Lectures on Christianity and the University, Stan Dragland and Joan Eichner, Avison’s long-time friend and editorial assistant, have provided a fascinating journey through the allusive prose of a strong and private poet.... [T]hese books are treasures. Reading between and below the lines, we encounter Avison as a woman whose life was extraordinary, not because she traveled to far-distant places or had heroic adventures, but because she identified with the lives of the poor and disadvantaged in her own city, lived in extreme simplicity, and delved deeply into the wellsprings of her faith and her poetry.’

—Deborah C. Bowen, Canadian Literature

Introduction or preface

When Margaret Avison died, on July 31, 2007, she had written a draft of her autobiography, had revised it, and then revised roughly half of it again. She left notes toward further revising a couple of the later chapters, and she left a file of materials that she had intended to work in, or to include in one way or another. Some of the primary composition was yet to come. Throughout the process, which slowed as she became more frail, she worked closely with her long-time friend and editorial assistant, Joan Eichner. Margaret sent the first rough draft to me, asking whether I thought the project was worth continuing. Of course it was. She pressed on, with me now involved as editor. She would revise a chapter and I would read it and send my suggestions for further revision, most of which she accepted, no doubt in consultation with Joan, who then incorporated the changes and returned them to me.

With the project left incomplete after Margaret’s death, Joan and I felt lucky to have gained a good sense of the sort of editorial suggestions, for clarity and directness, that Margaret would have welcomed. If not, we would have felt even more trepidation than we did in preparing the work for publication. We have made some changes for the sake of consistency in the text. In a very few places, we have silently corrected or omitted what we found to be an error of fact. Joan’s long-term close relationship with Margaret was an invaluable source of accuracy in matters like chronology. We have tried to keep our own presence minimal, but have on occasion contributed bracketed insertions and footnotes intended to inform or clarify or expand on some point or other.

We could not on our own integrate some of the materials that Margaret marked for inclusion, so we have prepared a ‘Documents’ appendix to the autobiography proper. To the material in this section, now and then risking some repetition (but with a gain of variation), we have added a few other texts -- essays, letters and interviews -- which flesh out the sense of Margaret Avison as person and poet. She was considering some of this material for inclusion; she thought all of it relevant. ‘Poets Learn From Poetry’ might have been part of this appendix, but Margaret always intended it to be her last chapter, whatever concluding remarks she might eventually have felt moved to make.

The letters to Eleanor Graham are fascinating to compare with briefer accounts in the autobiography proper of her Indiana summer school session. In most of the included letters, like the two essays on Tolstoy and the Doukhobors, especially the latter, Margaret is in full flight on artistic matters. She retrospectively devoted much less attention to these than to her history of employment and the importance of her faith. The glimpse of her epistolary skill recalls her friend Miriam Waddington, speaking of Contemporary Verse’s Alan Crawley. ‘His letters to me,’ she says, ‘as well as those from Livesay, Avison, and Marriott, are still so alive, so full of vitality, that I believe the correspondence between writers and editors of the forties -- if it is ever collected and collated -- will be every bit as exciting and intellectually varied as the letters of the Bloomsbury Group -- always, of course, allowing for the different Canadian context’ (Apartment Seven: Essays Selected and New, 24). We have made some cuts in the letters, always of innocuous material extraneous to this book. In a sense, of course, nothing is irrelevant. Margaret’s letters should some day be collected and published whole, at which time every iota they have to contribute to her story will be in print.

Discussion of including appendix material -- essays and interviews especially -- was begun while the text proper was still under preparation, but was necessarily left inconclusive. Austerity and self-effacement were characteristic of Margaret’s life and her attitude to her reputation, so we cannot be sure she would herself have included some ‘documents.’ Now and then, though, it was two against one: Joan and I ever so gently applying pressure and Margaret yielding. At other times, she resisted pleas for a little more story. With Margaret’s example of the keenest integrity burning in us, we have done our best not to take undue advantage of having the final say.

Margaret had in mind Not Not-There, a shorter version of the title of this book, for what became Momentary Dark (McClelland and Stewart, 2006). It was rejected at the time as unintelligible without context, leaving a longer version available for this book, where some of the context for it appears. The epigraph is the bones of it, now intelligible though fascinatingly enigmatic.

‘Too much autobiography,’ Margaret says in one of her letters to Miriam Waddington. The remark resonates with the injunction of Gladys Story, her grade nine teacher, to avoid for ten years the use of the first person pronoun in poetry. e.e. cummings has pointed out the impossibility of discovering ‘a single peripherally situated ego,’ meaning that everyone is, in a technical sense, egocentric. But he also said something else that Margaret would probably endorse, that ‘who I am is what I write’. Margaret lived for poetry, putting it second only to her Lord. The role of poet was of no interest to her. She even had trouble with public honours. Nobody who knew her would expect a confessional.

You hold in your hands a self-portrait by one of the country’s best and most revered poets, a woman of almost unparalleled humanity and humility. Because she could not finish it herself, it is not the book she envisioned. She would have wanted it all of a piece, not trailing an ellipsis of documents. Still, the book is almost all Margaret Avison, and that is always really something.

—Stan Dragland

One of Canada’s most respected poets, Margaret Avison was born in Galt, Ontario, lived in Western Canada in her childhood, and then in Toronto. In a productive career that stretched back to the 1940s, she produced seven books of poems, including her first collection, Winter Sun (1960), which she assembled in Chicago while she was there on a Guggenheim Fellowship, and which won the Governor General’s Award. No Time (Lancelot Press), a work that focussed on her interest in spiritual discovery and moral and religious values, also won the Governor General’s Award for 1990. Avison’s published poetry up to 2002 was gathered into Always Now: the Collected Poems (Porcupine’s Quill, 2003), including Concrete and Wild Carrot which won the 2003 Griffin Prize. Her most recent book, Listening, Last Poems, was published in 2009 by McClelland & Stewart.

Margaret Avison was the recipient of many awards including the Order of Canada and three honorary doctorates.

The Porcupine's Quill would like to acknowledge the support of the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. The financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) is also gratefully acknowledged.