The Porcupine's Quill

Celebrating forty years on the Main Street

of Erin Village, Wellington County

BOOKS IN PRINT

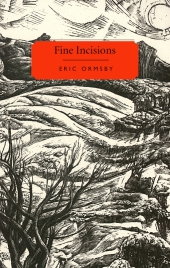

Fine Incisions by Eric Ormsby

Fine Incisions is a collection of twenty-four gracious, intelligent and occasionally fractious essays, wide-ranging in their interests and rigorous in their analyses. Ormsby’s reverence for language is luminously clear as he examines his international travels, the work of James Merrill, the state of North American literary criticism and more in a series of essays as vivacious as they are provocative.

‘A poem, I thought, is a physical object, as tactile as a statue. I began to consider poems in textual terms; there were shaggy surfaces, knobbly ones, mere veneers as sleek as glassine, but my favourites were those in which a complex and tensile music prevailed....’

Eric Ormsby, that gracious, intelligent and occasionally fractious poet, has produced another vigorous collection of essays to shake North American literary criticism from its lethargy. Opinionated and hilarious, Ormsby indulges his wide-ranging interests and discusses writers from Bob Dylan to S. D. Goitein, La Fontaine to Leo Tolstoy. Fine Incisions also draws connections between Ormsby’s literary criticism and his travel writing; as his essay ‘Shadow Language’ notes, the music of another language can seep pleasurably into a writer’s work (and, as Ormsby also notes, the lack of such linguistic overlap cheapens much of contemporary poetry!).

Although the topics vary widely, Ormsby’s viewpoint remains sharp and uncompromising, and his familiarity with North American, British and Arabic literary cultures informs each essay and leads to new and provocative reflection. Most of all, each essay is an expression of Ormsby’s own romance with language, and his devotion is clear in his adamant insistence on all writers’ very best.

2012—ForeWord Magazine Book of the Year,

Commended

Table of contents

Preface

Shadow Language: Foreign Accents in English Poetry

Passionate Syntax (William Butler Yeats)

The King of Never-To-Be (Walter De la Mare)

Butterfly on a Wheel (Bob Dylan)

Gilded Totems (James Merrill)

Mosquitoes in Eden (Richard Outram)

Ultimate Distillations (Daryl Hine)

Ancient Chills (Elizabeth Bishop)

An Austere Opulence (Geoffrey Hill)

Fine Incisions: Reflections on Reviewing

Delousing the Soul (J.-K. Huysmans)

The House in his Mind (William Maxwell)

Secret Lightning-Flashes (Leo Tolstoy)

The View from a Falling House (Katherine Anne Porter)

The Disaster Parade (Richard Yates)

Waiting for the Grammarians (C. P. Cavafy)

Ambitious Diminutives (La Fontaine)

Prague of a Hundred Towers

Two Letters from Prague:

Nostalgia for Bad Times (1999)

Waiting for the Golden Pig (2004)

Fabulous Cities

In Search of al-Majâtî

The Happiest Man in Morocco

The Born Schoolmaster (S. D. Goitein)

Review text

‘"The critic", writes Eric Ormsby, "must stimulate curiosity but he or she must also appeal to our innate sense of justice. Like it or not, the critic is a judge...We may flinch from the ’judgmental’ but at the same time, I think, we’re strangely elated, as well as reassured, when we see justice done, even in so small a matter as a review; it sets the world momentarily aright."

‘Fine Incisions is Ormsby’s second collection of essays-critical reviews, mostly, of poets and writers-and his judicious eye is certainly at work here. One feels one is following Ormsby through his reading program, digesting the old masters in turn: Yeats, Merrill, Cavafy, Maxwell, Porter, Tolstoy. He is no toady; as he writes about Elizabeth Bishop: "Still, it should be possible to admire Bishop’s genuine, and considerable, achievement without treating her every scribble as holy writ."

‘This stance is perhaps why Ormsby is described as "occasionally fractious" on the book’s blurb. If standing for old-fashioned standards in an age when every opinion is assigned equal value makes Ormsby fractious, then so be it. But his scholarship, his evident love of language, and his tone-opinions offered straight up without condescension or buttering up-lend credibility to his discernments. The range of his interests adds to his trustworthiness; he does not appear to be issuing judgments from an ivory tower. Whether or not Bob Dylan is a poet interests him as much as the "ethically seamless" world of animals and people in Jean de La Fontaine’s fables. He stands for another old-fashioned idea: books are not just for consuming, but for thinking about. Reading these essays will likely have the reader scribbling a new list of books to read, and Fine Incisions is the kind of book one wants to have handy for companionable reference.

‘Ormsby’s accomplishments are varied: Widely published as a journalist covering history, science, natural history, and religion, he is the author of six poetry collections, and an academic specializing in Islamist thought who has served at Princeton, McGill, and at the Institute of Ismaili Studies. His vita and the persuasive force of his writing amply qualify him as a critic.

‘But there’s more. As the collection progresses, Ormsby’s pilgrim soul comes into sharper focus. For him, words, like the tales of Shaharazad, "set the world right again before we sleep. They stand like fabulous cities against the encroachments of the dark". He searches Morocco for the poet Ahmad al-Maĵatî, whose lines seem to fall easily from the lips of Moroccans, but who, and whose books, are nowhere to be found. And then, in "The Happiest Man in Morroco", Ormsby is taken to meet "a pure soul", an an-nafs azzakiya, named Abd as-Slam, living in poverty in a cubbyhole above the market. Ormsby is captivated by the man’s simple intensity of attention.

‘Ormsby has just seen the exquisite ruin of Morocco’s Royal Library, a symbol of the destruction that awaits even the mighty. He muses, "where is there now, anywhere, a book whose magic will safeguard us?" And "in the presence of this ’pure soul’...I found nothing of what books had prepared me for". Ormsby perceives as-Slam’s happiness, perhaps the "strangest and least understood" of emotions, and that happiness stays with him "like the piercing after-fragrance of some rare perfume".

‘In this move beyond books, Ormsby subtly shifts the entire collection; not only a companion for a literary life, it has something to say about life itself.

—Teresa Scollon, Forewordreviews.com

Review quote

‘... Ormsby is one of the two or three best English-language poets we [Canada] can fairly lay claim to. A fact that should be recognized someday.’

—Alex Good & Steven W. Beattie, The Afterword

Review quote

‘A review like this one can only brush the surface of a collection so rich. And it’s simply impossible to praise it sufficiently. Its rare erudition and worldliness provide perfect ballast for the chiseled sentences of the essays, which flicker and snap with the energy of live wires. Ormsby borrows his title from a poem by Emily Dickinson, and does her honor in these essays that have the penetration of literal incisions, openings that cut deep into mystery, opening it to reveal all its shining interior.’

—Roger Sauls, Rover Arts

Review quote

Culture is not something so easily broken down. Fine Incisions is a study of literature and culture from Eric Ormsby, as he discusses North American Literary criticism and hopes to challenge it to rise to the challenge, as he mixes in memoir with his own studies of culture, language, literature, and so much more. A poet by trade, Ormsby’s writing is sure to draw readers in, and his stories and discussions will resonate with any, critic and non-critic alike. Fine Incisions is a strong addition to any literary criticism collection, enthusiastically recommended.

—Mary Cowper, Midwest Book Review

Previous review quote

‘Always, with Ormsby, things come down to the primacy of the word -- the sounds which shape and give ultimate authority. This is refreshing. It’s sophisticated yet not done in a complex or over-technical way. It helps to eliminate the general and abstract at the same time as it shows the way such things can and do transform the ordinary into something greater, more permanent, able, through the shaping, to encompass and embody experience. It’s admirable criticism and scholarship, certainly, but with the added dimensions of a poet’s working knowledge, of fluent multilingual abilities, and a determined search for the almost sacramental autonomy of word and form. It’s a heady brew.’

—Chris Wiseman, Books in Canada

Previous review quote

‘From the heights of a sand dune in the desert to the achievements of Hart Crane and the minutae of a letter by Marianne Moore, Ormsby presents us with a world that is always fresh, and continually fascinating.’

—Ian Ferrier, Montreal Review of Books

Excerpt from book

Butterfly on a Wheel: Bob Dylan

Whether writing on Tennyson, Eliot, Housman, Beckett, or many others, Christopher Ricks has always been a critic of exceptional learning and aplomb; that he has been generally given to a somewhat oblique, even eccentric angle of view -- embarrassment in Keats, the subtleties of punctuation in Geoffrey Hill -- has been to his credit, for while he is in one sense a traditional textual expert of rare authority (witness his editions of Tennyson and T. S. Eliot’s smuttier verses), he has also exhibited a delightful ability to surprise. His new book is no exception, less so in its erudition perhaps than in its surprises. Ricks, who recently completed a five-year term as the Oxford Professor of Poetry, has always been smitten with Bob Dylan; even in The Force of Poetry, his 1984 collection of essays, he included considerations of the singer as a poet rather than as a popular performer. It is clear now that his infatuation with the singer -- the word is not too strong -- has been no passing fancy but constitutes an all-consuming passion. With his new book, Ricks reminds us, on virtually every page, that the word ‘fan’ derives from ‘fanatic.’

All of Ricks’s impressive analytical strengths are on display in Dylan’s Visions of Sin. There is no song, no lyric, no mumbled comment from an interview with Bob Dylan, all cited here with excruciating exactitude, that does not elicit from this most acute of auditors some elaborate and, at times, almost comically inflated gloss. Shakespeare, Milton, Donne, Keats, Larkin, and many others are adduced to shore up his case. While Ricks’s learning and range of reference remain as impressive as always, the very scale of the enterprise overwhelms its subject. It is hard to think of any singer or composer, however brilliant or original, whose work could stand up to the claims Ricks makes for Dylan: Schubert would have quailed with dismay, Noel Coward would for once have been speechless. There is in truth something annihilating in Ricks’s advocacy of Dylan; as I read I found myself wondering at moments if this book did not represent a strenuous effort at self-exorcism, as though subjecting the slightest song and the most casual utterance to such drastic dissection might free the fan at last from his fandom.

As he makes clear in several statements, which Ricks quotes approvingly, Dylan has always been an instinctual, unreflective composer. He is wary, and rightly so, of excessive speculation on ‘the artistic process’. Many of his songs, among them the most famous, have come to him seemingly out of nowhere, and he doesn’t care to track them to their sources. Spontaneity, or at least the aura of spontaneity, is crucial to the effect of the best songs, as is a kind of rambling vivacity; and yet, in his extended analyses, Ricks freights Dylan’s lyrics with so many allusions and references and echoes that the songs seem to have been composed in a graduate seminar rather than on the fly. If Dylan ever reads Ricks’s book he may find himself so paralyzed by self-consciousness that he never picks up his guitar again.

Ricks’s case is this: Bob Dylan is not simply a consummate performer and a marvellous lyricist who revolutionized popular music in America over the last several decades, but a poet and indeed, not just any poet, but a great one, worthy to stand alongside the most illustrious in the language. To make his case Ricks must first establish that Dylan is a poet and that he sees himself as such. Ricks asks, ‘But is Dylan a poet? For him, no problem.’ Ricks then quotes from Dylan’s ‘I Shall Be Free’:

Yippee! I’m a poet and I know it

Hope I don’t blow it.

These immortal lines somehow fail to convince me. But Ricks persists:

The case for denying Dylan the title of poet could not summarily, if at all, be made good by any open-minded close attention to the words and his ways with them. The case would need to begin with his medium, or rather with the mixed-media nature of song, as of drama. On the page, a poem controls its timing there and then.

Ricks then ushers in, of all people, T. S. Eliot, who he says ‘showed great savvy in maintaining that ‘‘Verse, whatever else it may or may not be, is itself a system of punctuation; the usual marks of punctuation themselves are differently employed.’’ ’ Eliot’s quite suggestive comment is used, however, only to buttress Ricks’s next statement that ‘a song is a different system of punctuation again.’ Well, maybe, but what does this prove? Not much, as it turns out, for Ricks has inserted the Eliot citation only to lead into Bob Dylan’s use of the word ‘punctuate’ in an interview. The interviewer asks him, ‘It’s the sound that you want?’ And Dylan replies, ‘Yeah, it’s the sound and the words. Words don’t interfere with it. They--they--punctuate it. You know, they give it purpose [Pause].’ So besotted is Ricks with Dylan that he can remark about this diffident and unassuming reply, ‘this is itself dramatic punctuation, though perfectly colloquial’ and then add, parenthetically, ‘and Dylan went on to say ‘‘Chekhov is my favourite writer.’’ ’ Come again? Ricks appears not to have noticed Dylan’s rather revealing statement that ‘words don’t interfere’; he sees more significance in that ‘[Pause]’ about which he comments ‘the train of thought being that punctuation, a system of pointing, gives point.’ At such passages in the book -- and there are, alas, many -- even the best disposed reader cannot help wondering what exactly Professor Ricks has been smoking.

I for one am perfectly prepared to acknowledge that Bob Dylan is a poet and sometimes a fine one. Certainly many of his lyrics are superior to much of what passes for poetry nowadays in America; they are marked by strong and sometimes subtle rhythms, they rhyme wittily, they deal with themes of general import rather than mere coterie or private concerns, and, best of all, they are remembered by people who don’t usually read poetry or even care about it. His songs have always been suspiciously literary; that, together with what Philip Larkin, in a review which Ricks cites, called his ‘cawing, derisive voice,’ helps to account for their novelty and appeal. But his poems on the page and his poems as sung are not quite the same thing. I would argue that it is virtually impossible for anyone who has heard ‘Desolation Row’ or ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ or indeed any of the well-known songs to read them purely as poems. To read the words (for anyone, that is, of my and Professor Ricks’s generation) is to conjure up Dylan’s voice as well as the tunes and the accompaniment, and to do so irresistibly. And I feel sure that if a Dylan ‘poem’ were to be declaimed straight at a poetry reading anywhere, the audience would immediately begin humming the tune. Of course, this doesn’t mean that they aren’t poems, as Ricks claims, but rather that they demand a different kind of reading. Ricks knows this and tries mightily, often invoking particular performances or recordings, but the fundamental problem remains and it weakens his argument.

As Ricks also knows, to write a learned tome about Dylan’s lyrics without the music is as misleading as it would be to analyze his tunes without regard to the words. Pretentious as it must sound, each song, even the slightest, is after all a Gesamtkunstwerk, in which melody, lyrics, and backup combine to produce the final effect, and this is as true of Bob Dylan as it is of Johnny Mercer or Irving Berlin. Moreover, Ricks almost completely ignores the musical milieu and context out of which Dylan’s art developed and says hardly anything about, say, the Blues. Anyone who has ever heard Blind Willie Johnson singing ‘Dark Was the Night’ knows that Dylan (who would be the first to acknowledge his indebtedness) has no monopoly on a sense of sin or a raspy and compelling voice.

Stripped of their music, too many of the lyrics lie flat on the page:

I wish that for just one time

You could stand inside my shoes

And just for that one moment

I could be you

Others read better but again depend for their intended effect on the music from which, in the end, they are inseparable. Take ‘Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’, a song which Ricks compares to Swinburne’s ‘Dolores’ and which opens:

With your mercury mouth in the missionary times

And your eyes like smoke and your prayers like rhymes

And your silver cross, and your voice like chimes

Oh, who among them do they think could bury you?

Seen on the page, the alliteration of the first line hums too emphatically, the threefold rhyme has a singsong quality and the fourth line scans (and reads) clumsily. But these very features of the stanza tip us off at once that this is not meant to be a read poem; we sense instinctively that we are encountering a song, not a formal poem. Our ears alert us that what weighs down the page will be lightened by the living voice and that the words, in fact, must be heavier and more obtrusive than normal in order to stand up to the musical accompaniment. As a result, and without being able to help it, we read such a poem differently than we read ‘Dolores’:

Cold eyelids that hide like a jewel,

Hard eyes that grow soft for an hour;

The heavy white limbs, and the cruel

Red mouth like a venomous flower.

Swinburne’s stanza, for all its conspicuous musicality, does not lend itself to song. In Swinburne, the music, for better or worse, is in the words; in Dylan, the words stand in a sort of anticipatory suspension, awaiting the music. In his exegesis of this song, which he calls ‘a masterpiece,’ Ricks deploys a formidable array of learned references, citing The Oxford English Dictionary (to gloss ‘mercury’), T. S. Eliot, Matthew Arnold, Keats, Carlyle, Tennyson, and the prophets Ezekiel and Isaiah, as well as Swinburne. But why Swinburne, or any of the others, is brought into the discussion is never made clear; the whole discussion is something of a tour de force without the tour. And while ransacking his sources Ricks often overlooks the obvious. He is puzzled by the phrase ‘mercury mouth’ which he opines may signify ‘a death-dealing poison’ without once considering that it may be the tremulous skittering of spilled mercury that is meant; in other words, the sad-eyed lady’s mouth is aquiver. (And while we’re at it, why not adduce Auden’s line ‘The mercury sank in the mouth of the dying day?’)

It matters little to Ricks that Dylan himself may be blissfully ignorant of all his supposed sources (or ‘analogues,’ as Ricks prefers to call them). The smallest smidgeon of a resemblance calls forth reams of commentary, much of it far-fetched. Consider, for example, Ricks’s comparison of Dylan’s ‘Lay, Lady, Lay’ with John Donne’s ‘To His Mistress Going to Bed’ .The Dylan song begins thus:

Lay, lady, lay, lay across my big brass bed

Stay, lady, stay, stay with your man awhile

Until the break of day, let me see you make him smile.

The professor in Ricks cannot refrain from noting the solecism of ‘lay’ which would be, as he puts it, coyly reverting to Latin, ‘Anglicè, lie across it.’ (I can’t say that I’ve ever heard anybody say, ‘lay across the bed’ but then I haven’t met the sad-eyed lady or her pals.) Ricks tries to excuse this by coyly pointing out that Dylan could hardly have written ‘Lie, Lady, Lie’ as this would be ‘men accusing of mendacity the fair sex’ -- never mind that accusations of mendacity aren’t exactly uncommon in popular music (has Ricks never heard ‘Your Cheatin’ Heart’?). When he comes to compare Dylan with Donne, however, Ricks truly clutches at straws, all of which are definitely blowin’ in the wind. In an unconvincing table he sets out the analogies; thus, both poets use the words ‘bed’ and ‘show’ and ‘world’ and ‘standing’ and ‘still,’ to mention but these. Ricks comments, ‘Donne’s poem might be a source but what matters is that it is an analogue. Great minds feel and think alike.’ It doesn’t occur to Ricks that even not-so-great minds tend to use the same words when welcoming a naked woman into their beds.

Ricks’s fatal penchant for exaggeration in everything to do with Bob Dylan the artist and the man mars his book, for all its learning and ingenuity and occasionally superb explications of certain songs. We read, for example, that ‘Bob Dylan is one of the great rhymesters of all time’. While Dylan does show verve and agility in his rhymes, all of which Ricks dutifully inventories, will we really compare him to such poets as Byron or Browning or Pope as a ‘rhymester’? Even the most cursory glance at any page of Don Juan or The Rape of the Lock gives the lie to Ricks’s claim. Again we are told that Dylan’s album Desire is ‘an inspired title for an album.’ Why? Because the word &‘desire’ is ‘a word that knows too much to argue or to judge: its lips are sealed.’ Sealed lips don’t bode well for an album of songs and what is particularly ‘inspired’ about the title? Ricks never explains; he merely asseverates. Perhaps most irritating are the occasional comparisons of Bob Dylan with Shakespeare, as when Ricks remarks in passing that Dylan’s ‘art is something else, not being a business but a vocation, even while -- like Shakespeare’s -- it earns his living.’ Even more amazingly, he can declare that ‘not since King Lear has there been so tensile a tissue of eyes and seeing ... as is woven through ‘‘Precious Angel.’’ ’ And elsewhere he states ‘within a performing art -- Shakespeare’s tragedies, Dylan’s songs -- the ear possesses an extraordinary compensation for its sacrifice of the particular certainty that the eye can command.’ I have no idea what Ricks means by this assertion but the casual equation of Shakespeare and Dylan, which forms a leitmotif of the whole book, induces a sense of vertigo compounded by equal parts of hilarity and incredulity.

Ricks structures his discussion of Dylan’s songs by grouping them in accord with the seven deadly sins (hence the title) followed by the four cardinal virtues (Justice, Prudence, Temperance, and Fortitude) and ‘the heavenly graces’ (Faith, Hope, and Charity). This is probably far too schematic, as he himself acknowledges, and he is forced to do a bit of stretching to make the songs fit into their appointed categories, but it isn’t preposterous and here Ricks, for all his vagaries, does make a convincing case. He is especially fine when he comes to discuss Dylan’s ‘Christian’ songs and the ‘born again’ phase in his career that occasioned such dismay among many fans. An avowed atheist, Ricks deals with the jubilantly Christian songs such as ‘Precious Angel’ or ‘Highway 61 Revisited’ with tact and insight, and his enviable command of scripture stands him in good stead in his explications. Of those who denounced Dylan for his new-found faith he remarks aptly that ‘most Dylan-lovers are presumed to be liberals, and the big trap for liberals is always that our liberalism may make us very illiberal about other people’s sometimes letting us all down by declining to be liberals. The illiberal liberal has a way of pretending that the page that he would rather not read is illegible.’

For the die-hard Dylan fan who comes to Ricks’s book fresh from the music, and without any particular literary preconceptions, Dylan’s Visions of Sin will no doubt prove eye-opening. The discussions of individual songs, however eccentric or even downright batty, are invariably interesting; even when Ricks overreaches, his comments on the poems he draws on as parallels -- whether by Larkin or Hardy or William Barnes or Longfellow -- stimulate and illumine. His rather breezy conversational style can become annoying and his addiction to puns off-putting (the worst may be ‘gendresult,’ an amalgam of ‘gender’ and ‘end-result,’ which I hope does not catch on), but he’s incapable of writing a dull page. If too often you hear the dim crunch of a butterfly being broken on a wheel, you’re inclined to forgive Ricks because of the deep, if immoderate, affection he holds for his subject. At the same time, and speaking only for myself, I just hope he doesn’t now move on to The Boss or The King.

—Eric Ormsby, Fine Incisions

Introduction or preface

In putting together this second selection of essays, all written at different times over the last dozen years, I’ve tried to avoid imposing an after-the-fact coherence. These are essays about certain poets and novelists, as well as other, less conspicuous figures, whose accomplishments I admire and in some cases, even love -- though not always uncritically. I’ve also included evocations of certain places -- Prague and Morocco -- which have been important to me. At first I thought that including these travel essays would provide a kind of counterfoil to the more purely literary pieces. I wanted to replace the smell of the inkpot -- well, the anodyne scent of the inkjet cartridge -- with the stink of real streets, the more pungent the better. But, as I discovered, these essays turned out to be as much about works of the imagination as about the places themselves.

Then again, to set fine but forgotten or unfashionable poets or novelists (like Walter de la Mare or J.K. Huysmans), beside such acknowledged luminaries as Tolstoy or Bob Dylan seemed to me a way of provoking interesting reverberations. I believe that the casual victims of passing fashion, or those whom fashion has never deigned to notice, may sometimes have more to teach us than the successful and the celebrated. In any case, as I argue in the title essay, a critichas an obligation to do justice to the unfairly forgotten, if only for our own delight. This is less a matter of redress than of reclamation.

The two portraits -- one of a great contemporary poet in full swing, the other of an equally great and much-loved scholar -- are my attempts to bring living voices, actual or remembered presences, into the mix. I wanted to rattle the more formal pieces a bit; however, I suspect that they’ve settled in together a bit too cozily. I hadn’t expected happenstance to be so shrewd. In the end, of course, whatever coherence -- or happy incoherence -- there may be in a collection of essays written over a period of years is perhaps best left for the reader to discover.

Thanks to my editors, particularly at The New Criterion and at Parnassus (the journals where most of these essays first appeared), I’ve enjoyed the freedom to pick my own subjects and to write about them pretty much as I wish; at the same time I’ve benefited from those same editors’ meticulous attention to matters of style as well as of accuracy -- accuracy of tone as much as of fact. At The New Criterion, Hilton Kramer and Roger Kimball have long been generous friends, as well as inspiring essayists in their own right, and I am sincerely grateful to them. I have a more specific debt of gratitude to another friend at The New Criterion, its Executive Editor, the brilliant poet and essayist David Yezzi. David first invited me to write for the magazine in 1999, and his constant support and encouragement, as well as his uncommon discernment, have been of inestimable value to me ever since. I dedicate this collection to him in thanks.

Both Herbert Leibowitz and Ben Downing, co-editors of Parnassus, have been steadfast friends and exemplary editors. I deeply appreciate the care they have lavished on my essays.

I am also grateful to another friend, the superb poet and critic Carmine Starnino, who invited me to put together this collection for The Porcupine’s Quill and has seen it through the press. His perceptive comments and his critical candor have helped to make this a better book than it might have been.

Finally, as always, I thank my wife Dr. Irena Murray. Whatever insight I may have into things Czech -- or indeed, into ‘‘magic Prague’’ itself -- I owe to her. She has saved me not only from egregious errors in Czech (those maddening accents!) but her native elegance of expression and her unfailing sense of style, in language as in life, have guided me throughout; and her love continues to sustain me.

—Eric Ormsby

Eric Ormsby’s poetry has appeared in most of the major journals in Canada, England and the U.S., including The New Yorker, Parnassus and The Oxford American. His first collection of poems, Bavarian Shrine and other poems (ECW Press, 1990), won the QSpell Award of 1991. In the following year he received an Ingram Merrill Foundation Award for ‘outstanding work as a poet’. His collection, Coastlines (ECW Press, 1992), was a finalist for the QSpell Award of that year. A sixth collection, Time’s Covenant, appeared in 2006 with Biblioasis. His work has been anthologized in The Norton Anthology of Poetry as well as in The Norton Introduction to Literature.

Eric and his wife Irena currently live in London, England.

The Porcupine's Quill would like to acknowledge the support of the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. The financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) is also gratefully acknowledged.