The Porcupine's Quill

Celebrating forty years on the Main Street

of Erin Village, Wellington County

BOOKS IN PRINT

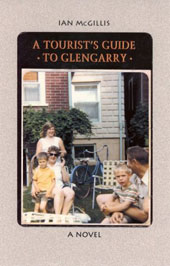

A Tourist's Guide to Glengarry by Ian McGillis

This book is a tribute to a real neighbourhood at a special point in time -- working class north Edmonton on the cusp of the oil boom. McGillis has drawn partly on figures from his own late 60s, early 70s childhood, including a maverick substitute teacher with a predilection for Eastern philosophy, a nine-year-old champion of civil rights, a chain-smoking ten-year-old son of anti-war radicals and baseball immortal Roberto Clemente.

Nine-year-old Neil McDonald has always wanted to write a book. Every time he tries, though, it comes out ‘like the Hardy Boys or something’. But when a maverick substitute teacher challenges him to record all the events and thoughts of a single day, the doors of creativity swing open. It helps that the day in question is, in Neil’s words, ‘pretty weird’. The time is the fall of 1971; the setting is lsquo;North America’s northernmost Metropolis’. The cast includes Neil, his best friend Keith and his gnome-like baba, a budding Black Power advocate, the heavy-smoking son of anti-war activists, and a very small boy wielding a very large axe in a public park. Neil thinks his day will climax with the broadcast of the first night game in World Series history, but what he’s in for is something much deeper, a surprise that will teach him much about the world and his place in it. In the end, Neil has his book. And it’s nothing at all like the Hardy Boys.

2003—Globe Top 100,

Commended

2004—Stephen Leacock Award,

Shortlisted

Review quote

‘ ‘‘Weird’’ and ‘‘neat’’ are neutral adjectives, but they betray something fundamental about Neil. Together they describe a sense of wonder, which often goes understated, and a certain ambivalence, the root of which is tolerance. With these two words, McGillis keeps himself and his readers on track, and in a genre which too often cedes artistic integrity to cliché, he refrains from playing the judgement card like a phony.’

—Andrew Steinmetz, Books in Canada

Review quote

‘Neil McDonald is the most eloquent nine-year-old you’ve ever heard. He’s the narrator of Ian McGillis’s captivating first novel, A Tourist’s Guide to Glengarry and he’s had quite a rough day -- encounters with drugs, booze, petty crime, teenage Italian girls, the threat of expulsion from school, enraged nuns, Black Sabbath, and puppy love are only a few of his worries. Set in 1971 Edmonton, a milieu that offers an uneasy blend of the cosmopolitan and the parochial, A Tourist’s Guide to Glengarry offers a guileless account of young Neil’s adventures, which involve a rapid-fire series of surprises, belly laughs, and kidney punches.’

—amazon.ca

Review quote

‘Yann Martel loves A Tourist’s Guide to Glengarry. In his cover blurb, the Booker-winning novelist compares it to the work of J. D. Salinger and Mark Twain. Martel’s invocation of these particular giants is not just a generous response to a good book. It aptly reflects Ian McGillis’s particular knack: piercing the armoured adult’s heart with the green arrow of a child’s.

‘Following an especially challenging day in the Edmonton suburb of Glengarry, nine-year-old Neil McDonald is urged by an eccentric teacher to record, as a writing exercise, everything that has happened to him since he tumbled from bed that morning. He does, and his singular diary forms the body of this debut, a dispatch from a mind still capable of wonder, yet sprouting tiny shoots of wisdom.

‘Neil’s prose cuts a finer line than you might expect, even from an exceptional nine-year-old. This small stretch ensures the book’s success. Before you can figure out quite what McGillis is up to, what buttons he’s pushing, he’s suddenly refiring a host of dormant neurons. The results are sad and exhilarating at the same time -- sadness for time’s march, exhilaration for such rare expression. It feels like learning all over again how to see the world and us in it -- how to share, to err, to rue and to move on.’

—Jim Bartley, Globe and Mail

Review quote

‘A Tourist’s Guide to Glengarry may do for Glengarry what Mark Twain, Margaret Mitchell, or William Faulkner did for the South.’

—Barry Hammond, Legacy

Flap copy

‘If the memory of childhood has lapsed, let this book be the antidote. A day in the life of a kid has never been so exquisitely, so magically, nor perhaps so comically, portrayed. Gazing through a child’s ViewFinder, our sad world is renewed and made wondrous again, which, as Ian McGillis reminds us, is the true import of childhood.’

—Trevor Ferguson

Back cover copy

‘If J.D. Salinger or Mark Twain had lived in Edmonton, they might have written A Tourist’s Guide to Glengarry. Prepare to slip into the mind of a nine-year-old. Prepare for a trip like Huckleberry Finn’s, except here it is not a river that is travelled but a single day in the life of little Neil McDonald. Prepare for a story that is simple, deep, psychologically dead-on, minutely observed yet worldly -- and very funny.’

—Yann Martel

Feature

An Interview With Author Ian McGillis

By Norm Frizzell, Centre for Reading & the Arts, Edmonton Public Library

‘Word of mouth’, strange term that it is, can be a powerful phenomenon. Once in a while a book comes along that compels one satisfied reader to spread the word to another, ‘You have to read this’. In the Canadian publishing industry many fine books are published that sink without a trace, due to a lack of public awareness and media presence, especially with smaller publishers. A grass root, word of mouth movement can save a fine book from the clearance table. For many months now, such a movement has kept Ian McGillis’ A Tourist’s Guide To Glengarry on top of the best sellers list compiled by Edmonton bookstores. The novel describes the events that take place within a single day (October 13, 1971) as seen through the eyes of one Neil McDonald, a nine-year-old boy growing up in the Glengarry district of Edmonton. Amusing and insightful with many cultural signposts both local and beyond along the way, Edmontonians have taken the book to heart, producing for the author a rare Canadian publishing event, a successful first novel.

Raised in Edmonton, Ian currently lives in Montreal. On a recent visit to Edmonton, Ian was able to spend an afternoon in the south side Sugar Bowl Café (where the book was actually written) sharing his thoughts on the book; it’s creation, reactions, and future projects.

The idea of writing a book had always been in the back of his mind, but it was in the Sugar Bowl on October 27, 1996, the day after the end of the Yankee-Braves World Series, that the process actually began:

‘Maybe it was having watched the baseball game the day before, but I thought of Roberto Clemente and how much it meant to me to get that card and especially with him dying a year after that (1972). I just thought I’d try to write in the voice of that kid who was trying to find that card. I decided to limit it to a day, and to limit it completely to that kid’s voice.’

Once he got started, Ian wrote the book straight through in a linear fashion without the agonizing rewrites that plague many an author’s attempts.

‘I tried to, as much as possible, recreate what that kid’s thought process would have been in the course of a day. I didn’t want to cheat on that by making some clever revision later on. It was almost like an experiment in linear prose. Although that sounds pretentious, I wanted to see how far I could take that single voice and concept.’

Pretentious is the last thing you would call this book. Although it is obvious that the ‘kid’, Neil, is based on the author and his life experiences, Ian is quick to point out that the book is a novel, not a memoir. Some characters are based on people from other periods in Ian’s life. Daniela is based on a girl Ian knew in high school. The gym teacher, Mr. Newcombe, is based on an Australian teacher who taught some of Ian’s older siblings. Every location mentioned in the book has an exact parallel in the real world.

‘I wanted people, theoretically, to be able to walk around Glengarry with a copy of the book and say ‘‘here’s that corner’’, and they could. The neighborhood hasn’t really changed at all. Some of the shops have different owners now, but most of the locations are exactly the same. There hasn’t been any new construction or anything torn down in that neighborhood in the last 32 years.’

For those unfamiliar, the Glengarry neighborhood is located in north central Edmonton, south of 137 Avenue and north of 132 Avenue, between 97 Street and 82 Street. Ian and his family moved there in 1962, from Hull, Quebec where Ian was born earlier that year.

‘137th Avenue was basically where the city ended. There were farms on the other side of the street. As I was growing up they started building places like Dickensfield and Londonderry a bit further down. The makeup of the neighborhood was upper blue collar to lower-lower middle class. Most of the fathers were trades people with an occasional teacher or something. The mothers were mostly housewives, which I talk about in the book. It was the end of that era, where most mothers stayed at home. The few working mothers that I was aware of at that time were from some other different kind of family setup where either the father wasn’t around for some mysterious reason or there was some kind of family turmoil going on, so the mother had to work.’

‘Edmonton was more isolated then, which is good and bad. Good in that people took more pride in their own little scene or culture and we didn’t necessarily feel we had to ape the United States. This was pre-cable TV, so even though a lot of the programming on the channels we had was American, there was also a little hierarchy of local celebrities. The host of Popcorn Playhouse, at the time, was like a god to us.’

‘There was a sense of a city and a community being built by the people who lived in it. In the case of a place like Glengarry, the first residents literally built the neighborhood. A lot of it was co-op housing and the owners had built their homes. Everybody had moved in and got their start at the same time, so there was a real bond. It felt like you were almost settlers. You would look across the street and there would be farms. I don’t know if you really get that anymore in these great big new subdivisions that go up.’

With less outside media influences, the printed word played an important role in Ian’s early years:

‘There was a general feeling of a huge adventure to go to the library or when the bookmobile came to town. Getting our hands on some new books for my friends and I was the closest thing to traveling. We weren’t of an income group that took off to some glamorous place every summer, so we got to know the world around us through books, National Geographics, that sort of thing. It was pre-multimedia age. Sure, we had TV and we all had a few records and the radio, but I think our number one entertainment source was still the printed word, including comic books.’

Ian’s favorite book that he associates with the library from this time period is The Horse Who Played Center Field by Hal Higdon. In Ian’s book, Neil took it out of the school library, but in reality Ian borrowed it from the downtown library when he was eight.

‘I remember thinking at the time it was the first sort of adult book, in that it was long, had no pictures, and the type was fairly small, that I read all the way through. It was about baseball, which I was fanatically into at that time, but it was also kind of a kid’s book in that there was a horse on this baseball team, which is obviously not true. I think the book is long since out of print. One dream of mine is that the people who read my book might create a demand for that book to come back into print.’

Ian has certainly found a demand for his own book. When he began the book it seemed only natural to set it in Edmonton. Some of the implications of this only became clear as he was finishing the book and getting it published.

‘I literally couldn’t think of another novel set in that period or level of society in Edmonton. I couldn’t think of another single example. It’s a great feeling of having filled that void. People have a basic need and desire to read stories set in places they at least recognize even if they can’t literally, personally identify with them. We get conditioned to thinking that stories only happen in certain exciting places, or Cape Breton or something where everybody’s poor and everything’s picturesque. I just thought my upbringing is as full of enough interesting experiences as anybody else’s. I’m just going to try and set it down the way it was, as close to it as I could recreate and have faith that people would be able to relate to it and it seems that they can. There’s an overwhelming sense of gratitude from people who come up to me at signings, not only saying how much they liked the book, but really thanking me and getting very emotional in some cases that someone had put their experience down on paper.’

Ian had basically completed the book while still living in Edmonton, just before moving to Montreal. The completed manuscript then sat in a drawer for a couple of years. Through a series of coincidences it ended up in the hands of a publisher (Porcupine’s Quill) and they accepted it in the summer of 2000. The book wasn’t actually published until the fall of 2002. In the meantime, during the winter of 2001, Ian showed the manuscript to another struggling (at the time) author who lived down the block, Yann Martel.

‘I didn’t really know him all that well, we had chatted a few times. I thought I had nothing to lose. I didn’t think he’d even read it, let alone like it.’

Yann obviously likes the book. On the back cover of Ian’s book is a quote from the Booker prize winning author praising the book: ‘If J.D. Salinger or Mark Twain had lived in Edmonton, they might have written A Tourist’s Guide To Glengarry.’

High praise indeed and there’s a lesson for aspiring writers as Ian points out:

‘Don’t be shy. I’ve found writers to be a very supportive community. They’re not bitchy or backbiting. They’ll go out of their way to help, especially for aspiring writers.’

Ian has already begun work on his next book. Without giving away too many details, as it’s still very much a work in progress, the working title of the book is The Anglophile.

‘It’s about a guy obsessed with British culture, more specifically British music. He lives vicariously through the records and the novels that he reads. It takes place over a thirty-year span, the sixties to the nineties. It takes place over three different continents and has different narrators. In terms of form it’s as different from the first one as it could possibly be.’

The book will continue to explore Ian’s interest in pop music and the cultures around it. Ian was surprised that not many reviewers or interviewers mentioned the musical side of Tourist’s Guide.

‘Music is so crucial to this book. To me, it’s the single most important element. For every part of the book, there’s a specific song that sets the tone.’

Many people have commented on how easily the book could be made into a movie. There have been some ‘tentative expressions of interest’ from the movie industry but Ian can’t go into any details at this point. When pressed as to who he could envision playing the role of the young Neil McDonald, Ian thought one of the younger members of the Culkin clan, Kieran Culkin, who recently appeared in The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys, definitely looked the part. A younger version of Jason Schwartzman, the lead role in Rushmore, would be his ideal actor. That movie’s director, Wes Anderson, would be Ian’s choice for director.

‘Rushmore and The Royal Tenebaums are masterpieces. The musical sensibility, the songs that he always chooses for his soundtracks are so perfectly in tune with what I do.’ (So Wes, if you’re reading this, get in touch with Ian).

One final note, for the many fans of the first book, there could be a sequel down the road.

‘Maybe for my third book, now that it seems there could be a demand. I feel like I created this kid and to never write about him again would be like abandoning him. I’ve had thoughts of maybe picking up his life at about age fourteen or fifteen, late junior high. It’s not that much later in terms of actual time, but it’s a really fundamental shift in the way you see the world. It would inevitably be a sadder and a less innocent kind of book. The kid has an innocent sensibility but he’s going to be dealing with a lot more nasty stuff going on around him.’

It may be awhile before this book appears, but if it’s anything like A Tourist’s Guide To Glengarry, it will be well worth the wait.

Excerpt from book

A Strange Beginning

This is weird.

That’s what I was thinking, standing there in Irene’s, on my last night in Glengarry.

Just being in Irene’s was weird enough. It’s this little place over on 82nd Street. They call it a diner, but you don’t really see anybody dining in there, unless you call sucking on cigarettes and guzzling coffee dining. It’s a really long, thin room, like a one-lane bowling alley, with tables down one side, and a poster by the door of an upside-down monkey with a long tail saying ‘Hang in there, baby!’ Being there was weird for me because it was ten whole blocks from my house, it was dark outside, and I was by myself.

Another strange thing was who I saw sitting at the table by the window. It was Mr Baldwin, a substitute teacher who taught my grade four sometimes, and Mr Nedved, one of the janitors at St Paul’s, my school. You don’t expect to see teachers and janitors hanging out together, especially outside school, but these guys aren’t exactly your typical teacher and janitor. They didn’t notice me at first, so I walked a few tables past them.

It must have looked pretty funny to see this little kid standing in the middle of a diner at night blinking from all the smoke, because almost everybody stopped smoking and yakking for a second to look up at me. I started to wish I hadn’t gone in there, but it would have been chicken to just go out again. The jukebox was playing ‘Maggie May’, which was the number one song on the CHED countdown the week before. It’s this really long song, by a singer with a croaky voice, about a guy who skips school and hangs out in poolhalls. So I was trying to hide how nervous I was by concentrating on the song when I heard a loud voice from behind me.

— Hail, hail, the wandering bard!

It was Mr Baldwin. He was talking to me. I walked over.

— Welcome to our bohemian enclave, he said. A cup of absinthe?

Just like in school, I didn’t really know what Mr Baldwin was talking about. Half the time he’ll talk to you just like he’d talk to an adult, and it’s up to you to figure out what he’s saying. I don’t mind that, though. It’s kind of neat. He just assumes you’re smart. He pulled a chair over and nodded at me to sit down.

— So, what brings our pocket Tolstoy into this disreputable den? he asked.

— Tolstoy’s this writer guy from Russia. Mr Baldwin calls me that because a few weeks before, at the start of the school year, I told him I was thinking about writing a book. It’s one of those things you say and feel stupid about a minute later, but he took me seriously, and ever since then he’s talked to me like I was a real writer.

— I was just walking around, I said.

That wasn’t the whole truth, but you couldn’t call it a lie, either.

— Gathering material, no doubt, Mr Baldwin said. All grist for the mill, eh?

— Yeah. I guess.

I had no idea what he meant. Then he turned to Mr Nedved.

— I should tell you, Jacek, that our little friend here is no ordinary gum-chewing, slingshot-shooting tyke. He’s about to storm the ramparts of the literary establishment.

Mr Nedved looked like he didn’t exactly understand Mr Baldwin, either, probably because he’s still learning English. I could tell from the books on their table that that was why they were there, so Mr Nedved could get English lessons. He raised his eyebrows and smiled at me. That was neat, because he’s not a real smiley guy. He didn’t say anything, though.

The waitress came by and filled their coffee cups, and then Mr Baldwin gave me a serious look. I think it just occurred to him how unusual it was that I was there.

— If you don’t mind my saying so, you’re looking a tad troubled, he said.

— I’m okay, I said.

Actually, I wasn’t so okay, but it was a long story. I’d had a really weird day, and I’d sort of wandered into Irene’s without really knowing what I was doing. I didn’t want to interrupt the English lesson, though, so I didn’t get into it. Then Mr Baldwin stuck his finger in the air.

— Of course! he said. Writer’s block! What else could have you looking so flummoxed? The creative juices are dammed. The words just won’t come. Am I right?

— Yeah.

The funny thing was, I hadn’t even started this book I told him I was going to write. I like the idea of writing a book, but I can never think of stories.

— A word from the wise guy, said Mr Baldwin. There’s a little exercise for scribblers in your spot, recommended by no less than Hemingway himself.

Finally, I thought, I knew what he meant by something. Hemingway was this writer who also went fishing a lot. At home there was this old copy of Life magazine, with a picture of him smoking a cigar and holding a giant swordfish. He also did this thing they do in Spain where you get a bull mad at you and the bull chases you around trying to gore you. Later, he shot himself.

— What exercise is that? I asked.

I thought he meant stuff like jogging and push-ups.

— It’s a kind of plunger, if you will, for those in your predicament, he said. Simply choose a day, any day, and write down everything that happens to you.

— What do you mean, everything? I asked.

— The works.

— Even going to the bathroom and stuff?

— There’s no room for squeamishness in your trade, lad. The great writer follows his characters everywhere, even to the meditation room.

There he went again, from talking about the bathroom to some other room that’s not even in my house. Mr Nedved seemed confused, too. He kept drinking coffee.

— Should I write about just what I did, or what I thought about, too? I asked.

— My lad, these decisions are in your hands alone. Just tell it like it is. Remember Joyce. No bodily function is too low, nor any interior musing too lofty.

He’d lost me again. Who was this Joyce lady I was supposed to remember? I was starting to like his idea, though. It kind of solved my problem of not being able to make up stories. Whenever I try, it ends up sounding like I’m copying the Hardy Boys, and I don’t even like them. Maybe just writing stuff down would be interesting, at least for me. It was a pretty good time to do it, too, because the day I’d just had -- October 13th, 1971 -- was a pretty weird day, like I already mentioned.

— Okay, I’ll try it, I said.

I must have taken a long time to say it, because they were back into their English lesson. Mr Baldwin didn’t hear me at first.

— What’s that, young sir? he asked.

— I’m gonna try it.

— Excellent! Excellent! I feel honoured, indeed humbled, to have performed this small service to future centuries of readers. Take out thy quill, and may it serve thee well.

— Sure. Thanks.

I wanted to say more, but they were starting their lesson again, Mr Baldwin explaining to Mr Nedved how to order beer in English. So I stood up and tiptoed to the door. ‘Maggie May’ was still playing, it’s so long. Just as I was opening the door, I felt a hand on my shoulder. I turned around and it was Mr Nedved. He smiled at me and said something in Czechoslovakian. Then I left.

So now I’m back at home, sitting in the empty living room. It’s about midnight, and Mum and Dad and all my brothers and sisters are in bed. I’m not supposed to be up, because there’s a big day ahead of us tomorrow, but I really feel like writing this stuff down before I start forgetting everything. I’ve got Dad’s flashlight to see with. My pen is making a giant shadow on the wall where the painting of the blue heron used to be. It’s weird to think I might never see Mr Baldwin and Mr Nedved again, to show them what I’ve done.

Ian McGillis was born in Hull, Quebec, grew up in Edmonton, and now lives in Montreal, within hailing distance of Fairmount Bagels. He is a regular contributor to The Gazette and co-edits the Montreal Review of Books. His journalism has also appeared in The Globe and Mail and The National Post. A Tourist’s Guide to Glengarry is his first novel.

The Porcupine's Quill would like to acknowledge the support of the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. The financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) is also gratefully acknowledged.