The Porcupine's Quill

Celebrating forty years on the Main Street

of Erin Village, Wellington County

BOOKS IN PRINT

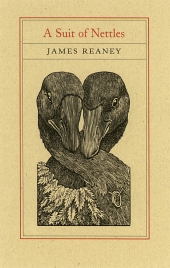

A Suit of Nettles by James Reaney

A new edition of James Reaney’s classic long poem which has been described, variously, as ‘the toughest and funniest, most literary and most serious long poem in English-Canadian literature’ (Germaine Warkentin) and conversely as ‘whimsical self-indulgence’ (W. J. Keith). A Suit of Nettles won the Governor General’s award for poetry in 1958.

The title of A Suit of Nettles was inspired by a German fairy tale. Seven suits of nettles are woven by the sister of seven brothers who have been changed into swans. When the time comes for the seven swans to put on their suits of nettles and regain human form, the arm of one suit is not finished. Consequently one brother always has one swan’s wing instead of an arm.

The poem, like Spenser’s Shepherd’s Calendar, is a sequence of pastoral eclogues, one for each month of the year, but here the dialogues are not between bucolic swans, they are between Ontario geese! Although the goose-eye view is bound to be somewhat restricting there is much carefully observed detail about farm houses, spring in a small pond, summer in a pasture and the small town Ontario Fall Fair. There are some ambitious satirical wallops at the English critical school headed by F. R. Leavis, at philosophy, progressive education and Canadian history. Here is a poet who believes in merry invective.

Lively, fanciful, humorous, this poem is also remarkable for its metrical ingenuity and skilful contrasts of harsh, brassy passages with mellifluous lyric. Parts of it were read on the CBC radio programme Anthology in the mid-1950s and the April Eclogue first appeared in The Tamarack Review.

2011—ForeWord Magazine Book of the Year,

Shortlisted

Quote from review of previous edition

‘... there are moments of poignant beauty like the conclusion of June or the winter song in November; there are farce, fantasy, religion, criticism, satire, all held together in a single controlling form. Mr Reaney has not tried to grapple with contemporary life in the raw, but merely to perfect his poem. And -- such is the perverse morality of art -- he has succeeded, as I think no poet has succeeded before, in bringing southern Ontario, surely one on the most inarticulate communities in human culture, into a brilliant imaginative focus.’

—Northrop Frye, University of Toronto Quarterly

Quote from review of previous edition

‘James Reaney’s A Suit of Nettles is a rare plant to find flourishing on any foundation these days.... It is rare because its satire isn’t urbane, wry, sly or implied.... He mocks fools rather than villains; he ridicules the results of excess. His pitch shifts agreeably; he is brash, merry, mythic, verbal, hilarious, by turns.’

—Marie Ponsot, Poetry (Chicago)

Quote from review of previous edition

‘Have just read James Reaney’s A Suit of Nettles, which surprised me beyond measure -- amused me and moved me. That enfant terrible has matured. Last time I saw him he seemed nothing more than a giggling boy. No boy could have written this remarkable, rich poem.’

—P K Page, Brazilian Journal

Review text

The title of James Reaney’s (1926--2008) book-length poem cycle, A Suit of Nettles, may ring a bell. Some may recall its acclaimed first publication in 1958; others will have read excerpts in the recent Essential James Reaney, also from Porcupine’s Quill (and shortlisted for the 2010 ForeWord Book of the Year prize). Still others will think of a tale from the Brothers Grimm -- about a princess who weaves suits of nettles to return six enchanted swans to human form. Yet if this allusion informs Reaney’s work, it is partly by way of contrast. For one thing, his protagonists are geese, not swans. For another, they never were human and never want to be. As the goose Mopsus sardonically puts it: ‘Here look at man. I’ll draw him in this dung.’

The joke ends up being on Mopsus, of course, when he and several other geese are butchered for Christmas dinner. But if this ending’s implications reflect the work’s scatological bent, they also play into its emphasis on cycles (vicious and otherwise). Echoing Edmund Spenser’s sixteenth-century Shepherd’s Calendar, Reaney divides his work into twelve chapters, one for each month. In keeping with pastoral protocol, these chapters display formally diverse poetic dialogues on a range of themes. Love features prominently, but so do Canadian history,1950s small-town life, and the conflict between traditional and progressive styles in education. For, whatever the geese think, this is the human world, albeit transformed by Reaney’s pen. Jim Westergard’s witty and elegant engravings in the new edition underscore this point.

Inevitably, given the nature of topical satire, not all of Reaney’s jokes still resonate. And yet, to use one of the book’s own metaphors, the merry-go-round of intellectual fashion sometimes comes full circle. Reaney’s comments on the Great Depression, for instance, now seem freshly relevant. Although it sometimes settles for clever patter, the book’s wit can also embody itself in memorable writing. High points include not only the boisterous invocation to the Muse of Satire, but also lyrics that strike a delicate balance between irony and genuine plaintiveness: ‘I am like a hollow tree / Where the owl & weasel hide / I am like a hollow tree / Dead in the forest of his brothers.’ The resulting book should appeal to a range of readers, including those interested in pastoral, in the work of Reaney’s mentor Northrop Frye, and in Canadian history and literature in general.

—Paul Franz, ForeWord Reviews

Review quote

‘A Suit of Nettles by James Reaney is a strange chimera of a book, equal parts Edmund Spenser (the craft), Hillaire Belloc (the wit), and olde tyme county fair (the mood). At once a formally rigorous and imaginatively capricious, A Suit of Nettles is a weird and wonderful achievement.’

—Paul Vermeersch, OpenBook Toronto

Review quote

‘As suggested by the calendar form itself, the book is chiefly concerned with time—not calendar time but mortal time, the linearity and finitude of human life set against the endless natural cycle of birth, decay, and death. ... A Suit of Nettles is finally a quest narrative, a search for spiritual and mental transcendence, for the transforming vision that might redeem mortal life from futility.’

—David Stacey, Canadian Literature

Author comments

This poem was written out of interest in a number of things: geese, country life in Ontario, Canada as an object of conversation and Edmund Spenser’s Shepherd’s Calendar. My publisher assures me that at the risk of insulting everyone’s intelligence I had better explain several matters beforehand.

The Shepherd’s Calendar, published in 1579, is a collection of dialogues between shepherds named Hobbinoll, Colin, Cuddie, Piers, Thomalin, Morrell, Thenot and so on. Since there is a dialogue for each month we are able to watch a complete English year pass before our eyes with its variety of weathers, crops and animals. Hobbinoll wishes to be Colin’s friend; Colin loves Rosalind for the entire calendar without any encouragement. At the end of the poem she has gone off with someone else. Cuddie is rather saucy to an old shepherd, Thenot, who reproves him with a fable about the Oak and the Briar. Willie and Thomalin discuss Cupid who has shot Thomalin in the heel and was once captured by Willie’s father in a fowler’s net. Piers and Palinode argue about Protestant and Catholic shepherds -- which are the better. In August Willie and Perigot put on a singing match judged by Cuddie and so on. There are plaintive love-sick eclogues caused by Colin’s miserable love affair, merry careless eclogues when the shepherds dance or sing and dark bitter eclogues when the sad state of the church and the poet are reviewed.

In A Suit of Nettles readers will notice that there are dialogues between geese named Mopsus, Branwell, Effie, Dorcas, Raymond, Duncan, Fanny and others. Branwell is the slightly ridiculous figure of melancholy itself wrapped up in a suit of nettles he has put on in order to emphasize his sorrow at a fair goose’s inattention. The reader will find fables, sestinas, singing matches, the passage of a year in the Ontario countryside -- many of the things already mentioned as being in the Shepherd’s Calendar. The Church satirized in A Suit of Nettles is that defined by Coleridge as comprising all the intellectual institutions of the age. These institutions sometimes nourish the educational theory and the literary criticism condemned in July and August, and the mental attitude described in May. Scrutumnus stands for Scrutiny, the famous critical quarterly edited by Dr F. R. Leavis which ceased to be published some years ago. May arises from an incident reported in Life concerning some fanatics in the populous Kentucky mountains. July springs from a fabulous CBC Citizens’ Forum in which Dr Hilda Neatby trounced a progressive educational theorist. The system of education suggested by Valancy’s remarks resembles that of the ancient Irish bards. In the long note ‘appended’ to August, for ‘God’s Universe’ and ‘God’s Tiger’ read Finnegan’s Wake and Blake’s Tiger, both victims of evaluation. In September, Bishop Bourget is the Pouter Pigeon, his victim is Guibord. Creighton’s history of Canada, Dominion of the North, gives you the facts, as well as the background for ‘Dante’s Inferno’, an attempt to compress Canadian history and geography into a single horrific scenic railway ride. Some of the things said about glaciers and their products have their source in a book by D.F. Putnam and L. J. Chapman called The Physiography of Southern Ontario. By the way, ‘Mome Fair’ is a careful imitation of the annual Fall Fair held in many small Ontario towns; the prize animals, birds and flowers as well as the carnival rides. Last of all, in Ontario there are, as I count them, forty-three counties, the forty-three fields mentioned in the second eclogue.

—James Reaney

Biographical note

At James Reaney’s funeral on June 14, 2008, his son’s tribute recalled his father as many things: poet, playwright, puppeteer, director, painter, historian, regionalist, scholar, student, wit, visionary, patriot, organic farmer, long-distance cyclist, shivaree-maker, dragon-slayer, and conversationalist (and that list is incomplete, giving less than half the terms used by Reaney’s son). In an energetic life that lasted almost eighty-two years, James Reaney had a major impact on the people and culture of southwestern Ontario, and that impact has been felt across Canada by those attuned to his poetry, his plays and his other achievements.

Born in 1926 on a farm near Stratford, Ontario, James (Jamie) Crerar Reaney was the only child of James Nesbitt Reaney and Elizabeth (née Crerar) Reaney. His mother’s ancestors were Highland Scots; his father’s were from Ulster. Once in Ontario, the families were variously Presbyterians, Plymouth Brethren, and Independent Gospel Hallers. Reaney’s father suffered from bouts of poor physical and mental health; years later, Reaney recalled how he ‘let me moon about the house, read books and practise music’. Reaney went to a one-room school in Elmhurst, Stratford Collegiate and Vocational Institute, and University College at the University of Toronto, achieving some freedom from his evangelical upbringing and receiving a B.A. in 1948, then an M.A. the following year. While in Toronto, he gained notoriety for his short story ‘The Box-Social’, in particular for its image of an aborted fetus. (Though as a student he published several stories in a rural or small-town Gothic vein, these wouldn’t be gathered into a book until 1996). Also in 1949, at the young age of 23, he won the first of his three Governor General’s Awards for his first poetry collection, The Red Heart, and began to teach English at the University of Manitoba. Two years later he married Colleen Thibaudeau, a former classmate and another poet, who would go on to publish memorable, innovative poetry collections such as The Martha Landscapes and The Artemesia Book. Their two sons, James Stewart and John, were born in 1952 and ’54. During his eleven years based in Manitoba, Reaney took a leave of absence to do a Ph.D. back at the University of Toronto, completing a dissertation, ‘The Influence of Spenser on Yeats’. While in Toronto, he finished his satirical and lyrical tour-de-force A Suit of Nettles. His and Colleen’s daughter, Susan, was born in 1959, the year before the family moved back permanently to Ontario.

In the fall he started teaching at the University of Western Ontario -- where he remained until his retirement in 1989 -- and published the first issue of his magazine Alphabet: A Semi-Annual Devoted to the Iconography of the Imagination. As an editor he published poets such as Jay Macpherson, Al Purdy, Milton Acorn, Margaret Atwood, and bpNichol. For its eleven-year duration, in its focus on the mythological aspects of literature, the magazine showed the powerful influence of Reaney’s teacher and mentor Northrop Frye. Through his teaching career Reaney was also dedicated to the culture and geography of his native region, devising courses such as ‘An ABC to Ontario Literature and Culture’. By the early 1960s Reaney was becoming recognized as a librettist (for Night-Blooming Cereus, a John Beckwith opera performed on the CBC in 1959) and a playwright, author of The Killdeer, One-Man Masque, and The Sun and the Moon. Tragedy struck the family in 1966 when Reaney’s son John died of meningitis at age 12.

Later in the decade and for the rest of his life, Reaney’s passion for theatre overshadowed his writing of poetry, resulting in many plays such as Colours in the Dark, Listen to the Wind and, most famously, The Donnellys, a non-linear, poetically charged trilogy inspired by a 19th-century Ontario Irish family killed by a hostile community. Reaney’s later theatrical creations and musical collaborations included two more projects with Beckwith: The Shivaree and -- including live action and eighteen five-foot-high puppets -- Crazy to Kill: A Detective Opera; the chamber opera Serinette, with music by Harry Somers; and a stage adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice Through the Looking-Glass. He was a vital, beloved force in theatre workshops and drama productions. His later poetry collections were published in 1990 and 2005. A few months before Reaney’s death, the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario, mounted a show called The Iconography of the Imagination, comprised of fifty landscapes, drawings and sketches that Reaney had completed during his creatively rich life.

—Brian Bartlett

Excerpt from book

Invocation to the Muse of Satire

With Punch’s stick (he holds it in his hand)

Beat fertility into a sterile land,

With hands of hawthorn branches in the winter,

And teeth of cold March rain that bite the soft snow,

And bristly porcupines on which the hunter sits for hair;

With skin of mildew and botfly holes poked through

In hide of long impounded, ancient cow,

With eyes whose tears have quotaed out to ice long ago,

Eyes bright as the critical light upon the white snow;

With arms of gallows wood beneath the bark

And torso made of a million hooked unhooking things,

And legs of stainless steel, knives & scythes bunched together,

And feet with harrows, and with discs for shoes-

Speak, Muse of Satire, to this broken pen

And from its blots and dribbling letter-strings

Unloose upon our farm & barnyard-medicine.

With those feet, dance upon their toes

With those legs, grasp them lovingly about the thighs

With that torso, press against their breasts

With those arms, hug them black and blue

With those eyes, look at them you love

With that cheek, rub against their cheeks

With that hair, put your head down in their laps

With those teeth, give forth playful bites

And shake their hands with hour-long explorations

Of their life and heart and mind-line,

But with that stick of which new ones spring ever

From that vine where it was barbarously cut off,

Beat them about the ears and the four senses

Until, like criminals lashed in famine time,

They bring forth something; until thy goad

Grows so warm it bursts into blossoms.

Here, lady, almost blind with seeing too much

Here is the land with spires and chimneys prickly,

Here is the east of the board and here the west,

Here may you enter and there, before you depart,

May you make the sky red with doom and axey wrath.

Has no one seen the country where your cure has nursed?

It is a land of upturned privies with occupants inside them

Crawling out through new tops like astonished moths

Bursting from their unusual, foul and dark cocoons.

James Reaney was born on a farm in South Easthope near Stratford, Ontario in 1926. He has won the Governor General’s Award three times for his poetry, though he is perhaps better-known as a playwright, especially for his landmark Donnelly trilogy (1974-75). Reaney’s theatrical adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice Through the Looking-Glass returned to the stage at Stratford in the summer of 1996.

His work includes: The Red Heart, poems, 1949; A suit of Nettles, poems, 1958; Twelve Letters to a Small Town, poems, 1962; The Killdeer & Other Plays, drama, 1962; Colours in the Dark, drama, 1969; Collected Poems, 1972; Listen to the Wind, drama, 1972; The Donnellys, a trilogy of plays, 1974-75; Baldoon (with C.H. Gervais), 1976; The Boy With an R in His Hand, young adult, 1980; Take the Big Picture, young adult, 1986; Alice Through the Looking-Glass, stage adaptation, 1994. James Reaney died in 2008.

For more information please visit the Author’s website »

The Porcupine's Quill would like to acknowledge the support of the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. The financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) is also gratefully acknowledged.