The Porcupine's Quill

Celebrating forty years on the Main Street

of Erin Village, Wellington County

BOOKS IN PRINT

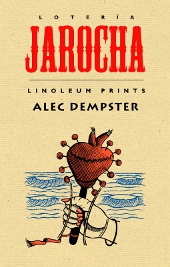

Loteria Jarocha by Alec Dempster

Lotería Jarocha assembles a series of linoleum-block prints created by Mexican-Canadian artist Alec Dempster after his return to his native Mexico in the mid-1990s. Discovering a lively genre of folk music from the Veracruz region, Dempster subsequently devoted himself to documenting his heritage with printmaking. The result is Lotería Jarocha, a collection of expressive images which catalogue Dempster’s encounter with the vibrant son jarocho culture of his birthplace.

In the mid-1990s, artist and musician Alec Dempster returned to Mexico, the place of his birth, and discovered son jarocho. A genre of folk music from the Veracruz region of Mexico, son jarocho originated in the 17th century with the confluence of Indigenous, African and European peoples. In Veracruz today, musicians can still be heard singing these traditional sones, passed down orally through the generations as themes or tropes, rather than songs with set lyrics. As Dempster immersed himself in the tradition, speaking and playing with rural musicians, his exploration of the culture resulted in a series of linoleum prints, each depicting a traditional son. Dempster’s imagery, playful and enigmatic, provides a window into a culture virtually unknown outside Mexico. In this stunning collection, Dempster lends his own voice to the prints for the first time, illustrating their genesis and origin in clear, unassuming prose. With Dempster as guide, Lotería Jarocha draws its reader into an infectious culture of music, laughter and dance.

2014—ForeWord IndieFab Book of the Year Award,

Shortlisted

2015—eLit Awards,

Commended

Table of contents

Introduction

El Aguanieve

El Ahualulco

El Balajú

La Bamba

El Borracho

La Bruja

El Buscapiés

El Butaquito

El Camotal

La Candela

El Canelo

El Capotín

El Cascabel

El Celoso

Los Chiles Verdes

El Coco

El Coconito

El Colás

El Conejo

La Culebra

El Cupido

Los Enanos

El Fandanguito

El Gallo

El Gavilancito

La Guacamaya

La Guanábana

El Guapo

El Huerfanito

La Iguana

La Indita

El Jarabe loco

El Juiles

La Lloroncita

La Manta

La María Chuchena

La Morena

Las Olas del Mar

El Pájaro Carpintero

El Pájaro Cú

El Palomo

Los Panaderos

Las Pascuas

El Perro

La Petenera

El Piojo

Los Poblanas

Los Pollos

El Presidente

El Sapo

La Sarna

La Tarasca

El Torero

El Torito

El Toro Zacamandú

El Trompo

La Tuza

El Valedor

El Zapateado

El Zopilote

Review text

Dempster’s linocut illustrations based on Mexican folk music are imaginative and fun, with writing that only adds to the enjoyment.

During his time in Veracruz, Mexico, musician and artist Alec Dempster began to create illustrations of various son jarocho, musical pieces in a folk style popular in the region. Dempster’s book Lotería Jarocha: Linoleum Prints combines sixty of his linocut illustrations--each based on a specific son--with artist’s notes about each. The result is an impressive collection art fans will appreciate.

Dempster has recorded multiple albums of son jarocho himself, and his linocuts have been used on multiple game boards for lotería--a bingo-like game that uses illustrations rather than numbers. He clearly loves the material, and that resonates in his artwork. His pieces have a whimsical quality that works for decorating lotería game boards, while also celebrating the music that inspired him.

Each of the drawings appears on a right-hand page, and Dempster supplements his artwork with just the right amount of text on the left-hand side. Depending on the print, he writes about the lyrics of the son that inspired it, the history of a particular piece of music or dance, or the personal experiences in Veracruz he evokes in his art. The book is beautifully produced, printed on a textured paper stock that helps the black-and-white images pop on the page, and gives the project a timeless appearance and tactile feel.

His anecdotes are brief and interesting, enhancing the reader’s understanding of each piece without becoming indulgent or repetitive. For a piece called "La Iguana," Dempster created a dancing man holding the titular lizard by the tale, and text describes the experience of watching the dance that accompanies this piece of music. "El Conejo" depicts an enormous rabbit leaping over a city, and is accompanied by the story of how rabbits became associated with the town of Santiago Tuxtla in Veracruz. In the case of "El Huerfanito," Dempster includes the lyrics of a son usually played at funerals, to accompany his plaintive portrait of a child kneeling in mournful prayer.

Dempster’s linocuts convey equally the sorrow of "El Huerfanito," the joy of the dance-based prints, the gentle absurdity of an absent-minded mole with a cane ("La Tuza"), and a pig using its snout to cook ("La Tarasca"). Dempster’s artwork is imaginative and fun to experience, and his writing only adds to the enjoyment.

—Jeff Fleischer, ForeWord Reviews

Review quote

Dempster’s collection of songs, linoleum prints, and prose descriptions create an amazing reminder that it is an error to treat folklore as simply sentimental material to be preserved as cultural history. Lotería Jarocha joyously posits folklore as resistance to a monolithic way of thinking or expressing oneself and an embrace of community and cultural diversity.

—Susan Smith Nash, World Literature Today

Excerpt from book

El Aguanieve

The rain in Santiago Tuxtla has two flavours: the torrid din of a summer downpour and the penetrating cold of a slow winter drizzle, called aguanieve. In December, damp weather often muffles the sound of nocturnal processions along streets and down alleyways when musicians gather, moving in multiple directions, each with a chorus of followers. Time and place are blurred by the mist and steady rain saturated with the collective incantation of a familiar refrain: ‘Oranges and limes, limes and lemons. The Virgin is more beautiful than all the flowers.’ The tranquility, however, is sometimes interrupted by northerly winds which invade the night with violent gusts, shattering windowpanes and rattling tin roofs. Many of the verses associated with this son mention tears, rain and the sea. Longing and departure are also common themes. Perhaps El Aguanieve originated along the coast as a lament for sailors out at sea, with other lyrics attaching themselves to it on its journey inland to places like Santiago Tuxtla where this son has been played for many generations.

El Balajú

Most people sing El Balajú without considering what the title might mean or what the son may be about. This is not surprising because balajú is an archaic word that has disappeared from the dictionary and common usage. Some clues may be found in the verse which is usually sung as an introduction.

Because he was a warriorThe maritime theme makes sense in relation to a definition published in 1859 referring to balajú as a schooner found in the Caribbean as well a type of boat used on the Bay of Biscay. The origin of certain verses and songs has been traced to very old songbooks. A songbook from Santiago Tuxtla includes a couple of pages of verses for El Balajú. One verse mentions The Port of Veracruz, Havana and El Muelle Inglés. The latter may refer to a historic port in Panama.

Balajú set off to sea.

This is what he said to his mate,

– Come and navigate with me.

Who’ll be first to cross the ocean?

Shall it be you? Shall it be me?

La Bamba

In 1958 Richie Valens rebranded the most emblematic of sones jarochos, in a rock and roll setting. He took his cue from early versions of La Bamba sung by musicians from Veracruz who had found a place in Mexico City’s burgeoning film industry and night club scene. Verses associated with La Bamba indicate that it may have originated in the Port of Veracruz during the seventeenth century when the population lived in fear of attacks by ‘Lorencillo’, a dreaded Dutch pirate. I first heard a more traditional interpretation of La Bamba in 1995 on a tape of field recordings made in Los Tuxtlas. A year later I heard a similar version after stumbling off a bus in Santiago Tuxtla. I had walked just a few blocks under the searing July sun when I came across a group of old musicians huddled together playing La Bamba under the protective shade of a storefront awning. They were from different communities taking part in the annual celebrations of the town’s patron saint. After attending a few fandangos I realized that La Bamba is still very much at the heart of the traditional son jarocho repertoire.

El Zapateado

Six short notes are enough to announce the arrival of El Zaptateado with a cavalcade of nails quickly following suit across rows of expectant strings. Two brazen chords are unleashed and begin to sway back and forth like a pendulum, creating the thick sound emanating from the fandango. Meanwhile, the guitarra de son weaves an endless string of melodic variations within the harmonic tug of war. Dancing couples take turns facing each other on the tarima to engage in the rhythmic dialogue. Singers jump into the fray with a piercing cry of ‘Ayyyyy!’ as a signal for the dancers to quieten their steps. In spite of the sudden lull each verse must be forcefully sung over the rumble of hard soled shoes, boots, and the cumulative drone of strings and staccato melodies. Throughout the son disparate voices ring out from all around the tarima, drawing from an old well of memorized poetry. The dancers wait impatiently on the sidelines for the end of each verse. Only then is there an opportunity for a change of partners, indicated by a gentle tap on the back.

Unpublished endorsement

‘In these animated linocut prints, Alec Dempster has given us vibrant, expressive visualized lyrics for songs known as sones jarochos that bring communities together to sing, dance, play games of chance – lotería – tell stories, and connect to a past that goes back centuries.’

—Tom Smart, author, curator, columnist and art gallery director

Unpublished endorsement

‘Se necesita un poco de gracia: you need some wit and grace to dance the most famous Jarocho song La Bamba and to understand it. Likewise the Lotería Jarocho graphics by Mexican/Canadian artist Alec Dempster are a witty combination of graceful and meaningful love declarations towards the Veracruzanian music and Mexican graphic art. At the same time illustrating the hidden meaning of the songs lyrics, the graphics refer to the very popular Mexican game of lotería, where instead of numbers as in the comparable Bingo game, words and names are to be collected on the board until a winner filled his board first.

‘The song titles and the verses illustrated by Alec Dempster in a magical and at the same time realistic manner solve the funny puzzles of many of the complex rimes. Love and attraction, longing and departing are the moving forces of any dance. You must let go preexisting ideas and be ready for the surprise of the unexpected hidden meanings to understand the dominating force of this music, which lives within a joyful world of mutual love between the dancing couples.’

—Helga Prignitz Poda, curator, art historian, and author of El Taller de Gráfica Popular en México 1937–1977

Unpublished endorsement

‘Alec Dempster has created una maravilla of text and image celebrating the musical culture of Mexico’s Vera Cruz region. With roots in the 19th century graphic art of Manilla and Posada, filtered through the reclamation of tradition of the revolutionary school of the twenties and the Taller de la Gráfica Popular artists that followed them, he has created a series of images that reflect both tradition and modernity. The texts combine anthropology, folklore, contemporary popular history and Alec’s own history and memory as a Mexican-Canadian. The combination is as fresh as a gulf morning breeze. All that’s missing is the music and Alec has made a CD of some of these songs – a CD that is well worth tracking down to listen to while you peruse this fine work. This is a great project that will delight both the reader with a casual interest in popular culture and the serious aficionado of Mexican music.’

—Gary Cristall, instructor at Capilano University and producer of music festivals, concerts, recordings and radio shows

Unpublished endorsement

‘Tradition is not static; it is something on which to build, to imagine, to create something new. In Lotería Jarocha, Alec Dempster embraces his passion for the son jarocho musical tradition of Veracruz, Mexico, and applies his printmaking artistic alchemy to create a fanciful collection of sixty annotated linocut images. Against the conceptual backdrop of the popular Mexican game lotería – a kind of bingo that combines proverbs with images of everyday Mexican life – Dempster transforms each piece of music into a visual riff on the piece’s theme. Music, game, art form and personal muse all resonate to produce a fresh and playful interpretation of folk tradition.’

—Daniel Sheehy, Ph.D., Director and Curator, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Introduction or preface

If you get the tarima

my answer is ‘Of course!’

Nicolas cried out with glee

while riding on his horse.

In the late 1990s, the young Mexican-Canadian artist, Alec Dempster, embraced son jarocho, a musical tradition with indigenous, European (primarily Spanish) and African components that emerged during the Spanish colonization of Mexico centuries earlier. Dempster was also attracted to the Mexican board game known as lotería, a game of chance of Italian origin, brought to Mexico from Spain in the eighteenth century. Both music and game provided the artist with ways to connect with the culture of his birthplace.

This book includes a suite of some sixty linocut prints by Dempster that can be appreciated as works of art, as illustrations for a board game and as emblematic expressions of lyrics for son jarocho songs, called sones, that can trace their origins some three hundred years into the Mexican past.

A visual artist and musician who was born in Mexico City in 1971, Dempster grew up in Toronto, where he received his formal training in art at York University. These prints were created when he resettled in Mexico a dozen years ago and began researching and learning son jarocho music. The learning process involved collecting oral histories, making field recordings with elderly musicians and playing with son jarocho musicians in a variety of settings all over the southern Mexican province of Veracruz.

This research resulted in Dempster’s self-published book, Faces of Son Jarocho (Rostros del son jarocho), a collection of interviews and linocut portraits of elderly musicians, singers and dancers from Veracruz. More than portraits, his prints pay homage to some of those who have devoted themselves to the local traditional music that has been a central part of their lives since childhood.

Prior to this research project, Dempster delved deeply into the son jarocho tradition. In 1999, he began recording the musical diversity of the region of south-east Mexico, and also began to illustrate the repertoire of traditional sones, before considering the format of the lotería game. Although Dempster’s main objective was to illustrate the son jarocho repertoire, and not to create lotería images, as he continued to work and began exhibiting the finished prints in art galleries, the original intention evolved into a lotería. When arranged on the walls of galleries in a grid the prints resembled a board game format more commonly associated with a bingo card. This similarity triggered an impulse to expand the series from its original thirty images to the sixty that are presented on the following pages.

Lotería is a game of chance played throughout Mexico. It is similar to bingo except that it involves a series of fifty-four pictures instead of numbers. As players watch their picture-filled game boards the caller pulls illustrated cards from a deck one at a time, and either recites a corresponding saying relating to the picture or simply announces the name printed on the card. Players with the matching pictures on their game boards place a marker on them. There are different ways to win, such as being the first player to place markers on all the images, filling the four corners or making a horizontal line or a cross.

To appreciate the full dimension of these prints, one needs to be aware of their relationship to the musical form of son jarocho. As traditional folk music, the songs grew from the fertile and diverse region and culture of Veracruz where a mix of cultures – European, indigenous and African – produced a dynamic form of dance music that blended these three distinct influences.

The Spanish introduced stringed instruments, such as violin, harp and the baroque guitar to the indigenous population. Over the next three centuries, the musical mix developed with indigenous Mexicans, mestizos and criollos developing their own regional variations of the musical instruments based on the European models. Most commonly associated with son jarocho is the small guitar-like instrument known as the jarana which is strummed; the guitar de son or requite jarocho, which is plucked with a long pick traditionally made from cow-horn; the harp; an octagonal frame drum, known as the pander jarocho; and the quijada, an instrument made from the jawbone of a donkey or horse.

Just as regional instrumentation developed, so too did distinct variations of musical form and dance traditions. Son huasteco from east-central Mexico, and the west coast’s son jaliciense (also known as mariachi) were two such variations; both are as unique and individual as son jarocho’s identifiable percussive rhythms, syncopation, vocal style, improvisational base and harmonic and rhythmic frameworks.

The term ‘jarocho’ as applied to the people and music of the region was originally used with disdain to characterize people of mixed indigenous and African origin; it eventually, however, became an assertion of pride. In colonial times, the Church sought to suppress certain sones jarochos because of their so-called ‘devilish qualities’ and some sones were banned, especially those which poked fun at religion, and because of the way in which they were danced. Double meanings, often of a sexual nature, are abundant in the verses.

The son jarocho repertoire consists of approximately one hundred individual songs, many of which Dempster has interpreted in his prints. They cover a wide range of themes, but there is the built-in requirement and expectation that jarocho musicians (of which Dempster is also one) improvise their own melodies, rhythms and verses, to such a degree that no two jarocho performances are identical. Variation and improvisation are key elements of a son jarocho performance, enabling the musician to channel the energy and enthusiasm of the audience immediately and directly.

The fandango – a gathering of musicians and dancers who collectively interpret son jarocho – is at the core of this tradition in which musicians play, sing and dance the zapateado atop a wooden platform called a tarima, much like that shown in Dempster’s linocut of El Colás. This reverie is governed by a common understanding of procedure and etiquette, such as sones to start the fandango, sones to play at dawn, sones for women or couples and sones with specific choreography.

At the heart of son jarocho and the fandango is its role in building and strengthening the community. There is a communal aspect to the musical form with its inclusion of professional and amateur musicians as well as the ability to bring together families, generations and different social classes. If you become interested in son jarocho, which Dempster also performs with his wife, Kali Niño, you join a community that is instant, present and has a legacy centuries old. It is a form whose animating principle is the need to share stories, laughter and, in the pithy, riddles and moral devices that are the lyrics to the songs, share some large or small life lesson.

In these lotería pictures Dempster tells us that as long as son jarocho musicians learn and hold onto the roots of the music and its social dimensions exemplified in prints like these, the tradition will thrive wherever the music is played.

—Tom Smart

Alec Dempster was born in Mexico City but moved to Toronto as a child. He later moved back to Mexico and settled in Xalapa, Veracruz, where his relief prints eventually became infused with the local tradition of son jarocho music. He has produced six CDs of son jarocho and has presented solo exhibitions of his prints throughout the world. Alec now lives in Toronto.

For more information please visit the Author’s website »

The Porcupine's Quill would like to acknowledge the support of the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. The financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) is also gratefully acknowledged.